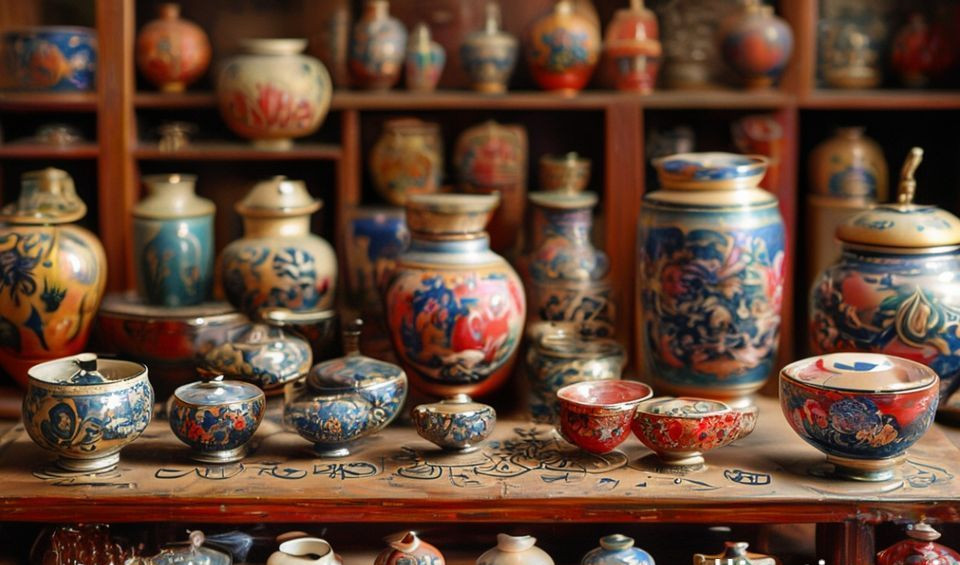

In the hushed galleries of museums and the careful light of private studies, a different kind of history speaks. It is not written in chronicles or decrees, but encoded in the glaze of a porcelain bowl, the patina of a bronze vessel, the precise warp of a scholar’s stone. These rare Chinese collectibles are more than artifacts; they are crystallized moments of cultural intent, where philosophy, belief, and social order were given tangible, enduring form. They exist at the intersection of sublime artistry, profound symbolism, and meticulous craft, offering a tactile connection to a worldview that sought harmony between humanity, nature, and the cosmos. To engage with them is to learn a visual and tactile language, one where every material, form, and motif is a deliberate character in a vast cultural text.

The Mandate of Material

To understand these objects is to listen to the dialogue between material and meaning. Jade, for instance, was never merely a beautiful stone. Its cool, unyielding texture, resonant ring when struck, and toughness that required patient abrasion rather than swift carving embodied the Confucian virtues of wisdom, integrity, justice, and moral fortitude. A simple white jade bi disc, polished over a lifetime to a waxy, luminous sheen, was a cosmic diagram—its central hole a gateway between heaven and earth, its circular form representing the heavens themselves. These discs, often found in Neolithic tombs, were symbols of divine authority and rank for millennia.

Similarly, the quest for the perfect celadon glaze during the Song dynasty was a spiritual and technical pursuit. The elusive ‘secret blue’ and ‘kingfisher green’ hues achieved at kilns like Longquan and Guan were not just aesthetic triumphs but attempts to capture the essence and virtue of jade in fired clay, to democratize its symbolic power. The clay itself was chosen with ritual care. The fine, white porcelain body from Jingdezhen, known as ‘white gold,’ was reserved for the imperial court, its flawless whiteness a mirror of political legitimacy and purity. This hierarchy of material was explicit: bronze for sacred ritual vessels, jade for embodying virtue, specific clays for imperial use, and more common materials for everyday life. The material was the first and most important word in the object’s statement.

Form Follows Cosmology: Symbolism in Shape and Decoration

Beyond the substance, the very shapes and surfaces of these objects are dense with coded meaning. The cong, a jade tube with a circular inner core and square outer section, is a prime example. Its form is believed to represent the ancient Chinese conception of a round heaven encompassing a square earth, making it a ritual object of immense cosmological power. Motifs are never merely decorative. A bronze ding tripod cauldron might be cast with a taotie mask—a stylized, confronting animal face—thought to ward off evil spirits. On porcelain, the lotus symbolizes purity and spiritual emergence from murky waters, while the peony stands for wealth and honor.

This symbolic language evolved through dynasties but retained a core grammar. During the Ming and Qing periods, visual puns and rebuses became popular. A bat (fu) represented good fortune, and five bats together signaled the “Five Blessings.” Painting a red bat on a vase was a wish for “vast good fortune” flooding in. A scene of a rooster, hen, and chicks was a hope for numerous offspring and family prosperity. To read an object is to decipher these layers of intention, where art served as a continuous visual prayer or statement of values.

An Archaeology of Use: From Imperial Altar to Scholar’s Desk

Rarity often lies not in ostentation, but in the intimacy of function and the gravity of ritual purpose. Consider the scholar’s objects, the wenfang sibao or “Four Treasures of the Study.” A tiny, ink-stained water dropper in the shape of a mountain, carved from a piece of flawed but evocative Duan stone, was a private universe. Its owner would grind his ink on a similarly prized inkstone, add water from the dropper, contemplating its form to infuse his calligraphy or painting with the spirit of the landscape. These tools—brushes of rabbit, wolf, or bamboo, wrist rests of zitan wood, inkstones—were extensions of the scholar’s self, worn smooth by daily ritual. Their value skyrockets when provenance reveals they were used by a known poet or painter; the physical object becomes a direct conduit to their creative act. A brush handle stained with ink is far more compelling than a pristine one.

Conversely, imperial artifacts carry the weight of prescribed ceremony and political theater. A set of twelve ritual jades from the Zhou dynasty, each with a specific shape (like the bi, cong, zhang) for a specific purpose in the worship of heaven, earth, and the four directions, is unimaginably rare. Their power derives from their flawless execution of a sacred, ancient template, a perfect alignment with cosmic order. A single misplaced line in the carving would render them powerless, mere stone. This principle extended to imperial porcelain. A commission for the Yongzheng Emperor would be produced in sets of dozens, with only the absolute perfection surviving; the rest were deliberately smashed and buried at the kiln site to maintain exclusivity and quality control. The object’s “use” was to manifest absolute authority and cosmological rightness.

“I once held a Ming dynasty Chenghua ‘chicken cup’ so thin it was translucent,” recounts Dr. Lin Mei, a curator specializing in ceramic history. “Its surface was painted with a simple cockerel and hen. My hand did not just feel porcelain. It felt the tremor of the painter’s brush, the incredible confidence required to apply such a perfect line to unfired glaze, knowing a single mistake would destroy weeks of work. In that moment, you are not analyzing an object. You are witnessing a conversation across five centuries—a whisper of skill, patience, and absolute focus that no document could ever record.”

This continuum of whispers—from the imperial kiln supervisor’s exacting standard to the scholar’s contemplative touch—forms a layered narrative. It is a history felt in the hand and seen in the subtle deviation from the norm, where the human element forever punctuates the ideal. A slightly uneven glaze, a repair with gold lacquer (kintsugi), or the natural wear on a handscroll roller tells a story of life, accident, and continued reverence.

The Modern Market: Navigating Authenticity and Appreciation

Today, the world of rare Chinese collectibles is a vibrant, global, and complex marketplace. Record-breaking auctions make headlines, such as the sale of a Song dynasty ceramic jar for over $26 million or a Zhou dynasty bronze ritual vessel for even more. According to a 2023 report by Statista, the Chinese art and antiques market remains a powerhouse, with strong demand from a growing cohort of domestic collectors. However, this enthusiasm exists alongside significant challenges, most notably forgery. The high stakes have fueled a sophisticated industry of reproduction, making expertise more critical than ever.

Authenticity is not a single checkpoint but a journey of evidence. Provenance—the documented history of ownership—is paramount. A piece that can be traced back to a reputable early 20th-century collection or is documented in an imperial inventory carries immense weight. Material analysis has become a key ally. Thermoluminescence testing can date ceramic pieces, while advanced spectroscopy can analyze the elemental composition of glazes and metals, often revealing anachronistic modern compounds. Stylistic analysis, comparing brushwork, form, and motif to undisputed benchmark pieces, remains the connoisseur’s core skill. As bodies like the International Council of Museums (ICOM) work to establish ethical guidelines, the market increasingly values transparency.

For the aspiring collector, education is the first and most important investment. “Start with the books, not the auctions,” advises Michael Chang, a seasoned collector in Hong Kong. “Handle pieces in museums that have been vetted. Understand the feeling of weight, the sound of porcelain, the look of age that isn’t just dirt. Find a niche—maybe 19th century export porcelain, or scholar’s rocks—and learn everything about it before you buy a single piece.” Building a relationship with a reputable specialist dealer or consultant can provide guidance and access to vetted pieces, offering a safer path into the field than anonymous online platforms.

Practical Insights for Engagement and Preservation

Engaging with this world does not require a multimillion-dollar budget. It begins with a shift in perspective. Visit museum collections with a focus: spend an hour looking only at Ming dynasty blue-and-white, comparing the density of the cobalt blue, the fluidity of the painting. Notice how imperial pieces have tighter, more controlled patterns, while those for the domestic market might have more playful, narrative scenes. Many major institutions, like the Metropolitan Museum of Art or the British Museum, offer extensive online collections with high-resolution images, allowing for detailed study from home.

If considering a purchase, due diligence is non-negotiable.

- Ask for a detailed condition report in writing, noting any restoration, cracks, or overpainting. Honest dealers will disclose this.

- Request provenance documentation as far back as possible. Gaps are red flags that require explanation.

- Consider scientific testing for any significant investment, understanding its limits and what it can prove. It is one tool among many.

- Buy from specialists who offer a clear guarantee of authenticity and a reasonable return period. Membership in professional bodies like the Art and Antique Dealers Association can be a positive indicator.

Preservation is an act of respect. Display ceramics away from direct sunlight, which can fade underglaze colors over decades. Maintain stable temperature and humidity—avoid placing items above active fireplaces or in damp basements. Handle all objects with clean, dry hands, supporting them from the base. For bronzes, a stable patina is desirable; aggressive polishing destroys historical value. The principles of preventive conservation emphasize stabilizing the environment to slow deterioration, a philosophy perfectly suited to caring for these objects at home.

Cultural Heritage in a Global Context

The circulation and collection of Chinese antiquities raise important questions about cultural heritage. The looting of archaeological sites to feed the market results in an irreparable loss of context, turning a historical document into an orphaned commodity. International frameworks, like the 1970 UNESCO Convention, aim to prevent the illicit import and export of cultural property. Repatriation cases, where museums return items taken under colonial duress or illegally excavated, are becoming more common, fostering a new dialogue about ownership and stewardship.

This evolving landscape suggests a modern model of collecting that balances appreciation with ethics. It involves supporting the legal market, demanding transparency, and respecting the cultural significance of objects beyond their monetary value. Some collectors now fund archaeological research or collaborate with source-country museums on exhibitions, shifting the role from private owner to public custodian. As noted in scholarly discourse, the focus is moving towards “shared heritage,” acknowledging the global interest in these works while recognizing their deep roots in Chinese civilization. Publications like the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians often explore the intersections of object history, cultural patrimony, and collection ethics.

The whisper from a Song dynasty celadon bowl or the silent authority of a Neolithic jade cong continues to speak. They tell of a culture that sought to embed its highest ideals into the very stuff of the earth, to make philosophy permanent. To collect, study, or simply appreciate these rare Chinese collectibles is to participate in an ongoing conversation—one that demands not just an eye for beauty, but a mind for history, a respect for craft, and an ethical compass. In their silent presence, they challenge us to be more thoughtful custodians of the past, ensuring its whispers are not drowned out by the clamor of commerce, but heard, understood, and passed on with care.

You may also like

Guangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cartHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartAncient Craftsmanship & ICH Herbal Beads Bracelet with Yellow Citrine & Silver Filigree Cloud-Patterned Luck-Boosting Beads

Original price was: $128.00.$89.00Current price is: $89.00. Add to cartAladdin’s Lamp Heat-Change Purple Clay Tea Pot

Original price was: $108.00.$78.00Current price is: $78.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartThe Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page