On a quiet shelf in a sunlit apartment, a blue and white porcelain vase holds a single branch of cherry blossom. It is not five centuries old. It was fired in a kiln last year, but its form, its cobalt patterns, its very weight in the hand speak of another time. This is the reality of the Ming dynasty porcelain replica: not a museum piece behind glass, but an object designed for the hand, the table, the lived-in space. Its value lies not in provenance, but in presence. It bridges a gap between the awe of history and the intimacy of daily life, inviting us to participate in a continuum of craftsmanship and utility that began in the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen.

The Grammar of Use: Form Follows Historical Function

True utility begins with understanding what the original object was meant to do. A Ming-era meiping (plum vase) was not merely decorative; its high shoulders and narrow mouth were designed to cradle a single flowering branch, keeping it upright and displayed. A replica that slouches or widens that aperture fails its primary function. The weight distribution of a Yongle-period stem cup—precise and balanced for elegant lifting—must be replicated not just for aesthetics, but for tactile satisfaction. When a modern potter recreates the thin, resonant body of a Chenghua ‘chicken cup’ replica, the goal is not fragility for its own sake, but that specific, thrilling delicacy that transforms the act of drinking tea into a conscious ritual.

Three key functional aspects often overlooked are thermal conductivity, acoustic properties, and stability. The way a porcelain cup moderates the heat of tea, feeling warm but not scorching, is a direct result of its material density and wall thinness—a feature perfected during the Ming dynasty. The subtle, high-pitched ‘ping’ emitted when flicking a fine piece is a hallmark of its vitrification and structural integrity. Furthermore, the flatness of a base or the subtle rounding of a foot ring, often invisible at first glance, was calculated for stability on the uneven surfaces of a scholar’s table, a concern just as relevant for today’s wooden dining tables. These are not arbitrary details but the encoded language of practical design, waiting to be deciphered through use.

The Modern Kiln: Techniques and Ethical Re-creation

Creating a faithful Ming dynasty porcelain replica is an exercise in historical empathy and technical prowess. It begins with the clay body itself. The distinctive, slightly creamy hue of Ming porcelain came from the unique kaolin and petuntse (porcelain stone) blends mined around Jingdezhen. Contemporary artisans either source similar local materials or carefully blend modern clays to approximate the color, texture, and plasticity of the original “white gold.”

The application of cobalt blue underglaze, the signature of Ming blue-and-white ware, is a particular art. Historically, cobalt was imported from the Middle East (known as ‘Mohammedan blue’), which produced the characteristic sapphire tones with occasional dark, speckled imperfections. Modern replicators must decide whether to use period-accurate, imported cobalt ores or modern, refined pigments to achieve the visual effect. The brushwork is another critical layer. Motifs like lotus blossoms, dragons, and cloud collars followed strict imperial conventions. A master painter spends years studying the pressure, flow, and spontaneity of Ming dynasty brushstrokes, which were confident and fluid rather than rigidly mechanical. As noted in a Metropolitan Museum of Art overview, the Ming era saw an unprecedented standardization of forms and decorations, a language that replica artists must learn to speak fluently.

The final and most dramatic stage is the firing. Traditional wood-burning mantou (steam bun) kilns created complex atmospheric conditions, leading to unpredictable and beautiful variations. Modern electric or gas kilns offer control but can sterilize the result. The most dedicated studios use replica kilns and wood-firing techniques, accepting that a certain percentage of pieces will warp or crack—a testament to the same risks Ming potters faced. This process raises a vital question: is the goal a perfect, sterile facsimile, or an object that captures the spirit, including its human imperfections? The latter often holds more soul.

From Kiln to Kitchen: The Journey into Daily Life

The journey of a high-quality replica from a collector’s cabinet into daily life is a deliberate and revealing one. Consider a pair of ‘blue and white’ replica bowls intended for actual dining. Their first test is the dishwasher. A glaze that mimics the soft sheen of Ming porcelain must also resist modern detergents and thermal shock. The cobalt underglaze decoration, painstakingly copied from a Wanli period design of lotus and carp, must not fade or craze under repeated washing. These are not concessions to modernity, but translations of durability. The original pieces were made to last, to be used; their replicas must do the same in a different technological context.

A collector in Shanghai might use a replica guan jar to store loose-leaf tea, noting how the tight-fitting lid, faithfully reproduced, preserves aroma far better than any modern canister. The object teaches through use: the way a brush washer’s well channels water, the heft of a correctly proportioned wine jug. It is a silent tutorial in historical ergonomics.

“We had a client,” shares ceramicist Liang Wei, “who ordered a replica of a Xuande doucai dish. She insisted on eating her breakfast from it every day. After a year, she wrote to me. She said she finally understood why the original dish had that specific, shallow curvature—it kept her fried egg from sliding. It was a design solution for a morning meal, centuries old. That’s when a copy stops being a copy and becomes an experience.” This anecdote underscores a vital point: the most profound understanding of these objects often comes not from academic study, but from sustained, ordinary handling.

The Collector’s Eye and the Modern Market

The market for Ming dynasty porcelain replicas is nuanced, spanning from affordable, mass-produced souvenirs to exquisite, limited-edition pieces by master artisans. For the serious enthusiast, understanding this landscape is key. High-end replicas often come with documentation detailing the original piece that inspired them, the materials used, and the firing process. These objects are not meant to deceive but to honor, and their value appreciates based on the artist’s reputation and the fidelity of the work.

Market data reflects a growing appreciation. A report on global artisan crafts indicates a rising demand for culturally significant, handcrafted items, with East Asian ceramics holding a prominent place. This trend is partly fueled by digital platforms that connect artisans in Jingdezhen directly with a global audience, demystifying the process and making these pieces more accessible than ever before. The replica thus becomes a tangible entry point into art history and connoisseurship.

Ethics are a constant companion in this space. Reputable makers and sellers are transparent, clearly labeling items as replicas or interpretations. The line between a tribute and a forgery is defined by intent. As the British Museum’s research on Ming trade illustrates, porcelain has always been a commodity of cultural exchange. Today’s ethical replica continues that tradition of sharing beauty, not appropriating history for fraudulent gain.

Practical Insights: Choosing and Living with Replicas

For those drawn to the idea of integrating a Ming dynasty porcelain replica into their home, a few practical considerations can guide the choice. First, define your intention. Is the piece for display, for occasional ritual use (like tea ceremony), or for robust daily service? This will dictate the required level of durability and influence your budget.

Seek artisans or studios that are transparent about their process. Do they use traditional materials and firing methods? What is their philosophy regarding accuracy versus interpretation? Examining close-up photographs of the glaze surface, brushwork detail, and foot ring can reveal much about the quality and care invested. Remember, a good replica should feel “right” in the hand—its balance, weight, and rim smoothness are immediate tactile tests.

Start with a single, versatile piece. A classic blue-and-white xiaokou (small-mouth) vase can hold flowers, brushes, or stand alone. A pair of simple cups encourages mindful drinking. Use them without fear. Wash them by hand with a soft cloth, using mild detergent, to preserve the glaze’s luster over decades. As you use them, you’ll begin to notice the subtle ways they interact with light, liquid, and food, creating a personal dialogue with the past that no museum visit can replicate.

Cultural Resonance and Global Dialogue

The phenomenon of the Ming porcelain replica exists at a fascinating cultural crossroads. Within China, it is part of a broader guochao (national trend) movement, where younger generations are re-engaging with traditional aesthetics. High-quality replicas allow for personal participation in this cultural revival, making a once-imperial art form accessible. Globally, these objects serve as ambassadors of a specific artistic zenith. They allow global audiences to appreciate a design sensibility that has influenced ceramics worldwide, from Delftware in the Netherlands to the wares of the English Staffordshire potteries.

This global exchange is not new. The Ming dynasty itself was a period of immense foreign trade, with porcelain being its most coveted export. Vast quantities were shipped to Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and later Europe, shaping tastes and inspiring local industries. Today’s replicas continue this dialogue, allowing a global community of enthusiasts to connect with a shared heritage of beauty and craftsmanship. As UNESCO recognizes in its efforts to safeguard intangible cultural heritage, the knowledge and skills behind such crafts are a living, evolving treasure. The replica is both a product and a perpetuator of this living tradition.

Material Science Meets Ancient Craft

Beneath the beauty of a Ming replica lies a fascinating story of material science. The durability and translucency of true porcelain, achieved during the Ming era, resulted from firing kaolin clay at temperatures exceeding 1300°C. Modern studies of ceramic stability help today’s artisans refine their mixes, but the core challenge remains the same: achieving maximum strength with ethereal thinness.

Research into historical production methods, such as analyses of glaze compositions published in journals like Archaeometry, provides a blueprint for modern recreations. This scientific approach helps distinguish between a visually similar copy and a functionally authentic replica. For instance, understanding the specific iron oxide content that gives certain Ming glazes their soft, ivory tone allows artisans to avoid modern chemical substitutes that might look right but feel wrong. This marriage of empirical data and traditional technique ensures the replica is truthful to its ancestor not just in spirit, but in substance.

Beyond the Object: The Replica as a Lens for Mindfulness

Ultimately, the deepest value of a Ming dynasty porcelain replica may be phenomenological. In a world of mass-produced, disposable goods, these objects demand and reward attention. They slow us down. Pouring tea from a replica ewer becomes a deliberate act of grace. Arranging a single stem in a meiping vase turns into a weekly meditation on form and transience. The object, through its historical DNA, encourages a state of mindfulness.

It reminds us that beauty and utility were never intended to be separate. The Ming craftsmen, working under imperial decree, sought perfection in service. A replica that fulfills its original purpose—holding wine, serving food, displaying a flower—completes a circle across time. It validates the original designer’s intent in a contemporary setting. The chip or fine hairline crack that may come with years of use (known as jin si tie xian or “gold thread and iron wire”) doesn’t diminish its value; it adds a new chapter to its story, integrating your own life into its narrative.

The quiet shelf in the sunlit apartment is therefore more than a display. It is an active site of cultural continuity. The replica vase holding the cherry blossom is in conversation with its 15th-century ancestors, not through the silent stare of identity, but through the shared, fulfilled purpose of elevating a simple moment. It proves that the legacy of Ming porcelain is not locked in history but is a living, usable, and profoundly human art, continually reborn in the kilns of the present and the homes of those who choose to live with history in their hands.

You may also like

The Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

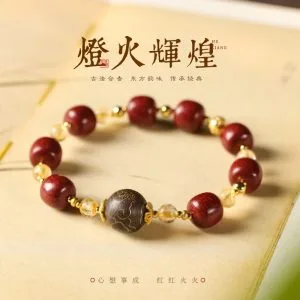

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartBambooSoundBoost Portable Amplifier

Original price was: $96.00.$66.00Current price is: $66.00. Add to cartHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartAncient Craftsmanship & ICH Herbal Beads Bracelet with Yellow Citrine & Silver Filigree Cloud-Patterned Luck-Boosting Beads

Original price was: $128.00.$89.00Current price is: $89.00. Add to cartGuangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cart