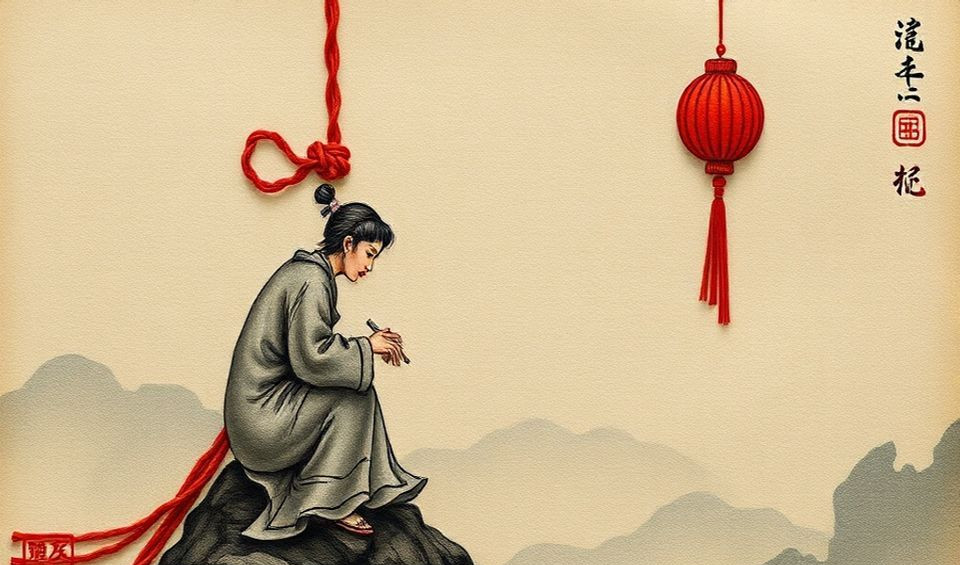

In the quiet corners of Chinese antiquity, where silk threads first learned to dance, a unique art form emerged from practical necessity. Fishermen secured their nets, scholars tied their scrolls, and warriors fastened their armor—each knot holding more than physical objects. These simple twists gradually transformed into complex symbols, carrying wishes, prayers, and cultural codes across generations. What began as functional fastenings evolved into a sophisticated visual language, encoding everything from social status to spiritual beliefs in meticulously crafted loops and weaves.

The Language of Loops

By the Tang Dynasty, around the 8th century, knotting had evolved beyond utility into sophisticated visual communication. Palace artisans developed over twenty distinct knot types, each with specific meanings and applications. The Pan Chang knot, with its endless looping pattern, represented eternal love and continuity. “We didn’t just tie knots,” explains cultural historian Dr. Lin Wei, “we wove our philosophy into them. The balance of yin and yang appears in the interplay of empty and filled spaces within each design.”

These creations adorned everything from imperial robes to musical instruments. A single ceremonial garment might feature thirty different knot variations, each positioned according to strict symbolic protocols. The double coin knot brought wealth, the mystic knot offered protection, and the good luck knot carried blessings for new beginnings. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, knot artistry reached its zenith, with artisans developing increasingly complex patterns that required days or weeks to complete. The craft became so refined that certain knots served as official seals or identification markers for imperial messengers traveling between provinces.

Colors That Speak

Beyond the intricate patterns, color selection conveyed layered messages. Red threads dominated celebratory occasions—weddings, births, and festivals—radiating joy and warding off misfortune. During mourning periods, blue and white knots appeared, their somber hues reflecting grief and remembrance.

Imperial yellow remained exclusive to the emperor’s household, while commoners employed vibrant combinations for everyday blessings. A merchant might hang a green and gold knot above their shop entrance, hoping to attract prosperity. Farmers tied red and yellow knots to farming tools before spring planting, seeking abundant harvests. The symbolism extended to material choices too—silk threads represented luxury and formal occasions, while cotton or hemp suited everyday use.

Modern artisan Zhang Min recalls her grandmother’s wisdom: “She taught me that the color must match the intention. A red thread for marriage, a gold thread for business, a purple thread for wisdom. The knots remember what our words sometimes forget.” This color vocabulary continues today, with contemporary artists sometimes introducing new shades while respecting traditional color associations.

Techniques and Tools of the Timeless Craft

Traditional Chinese knot art requires minimal tools but immense patience. Artisans typically work with a simple board, pins, and tweezers to manipulate the threads. The process begins with measuring and cutting silk or cotton cords, then anchoring one end while systematically weaving the other through intricate patterns. Each knot type follows specific sequences—some requiring up to thirty separate movements to complete.

Basic knots like the cloverleaf form the foundation for more complex designs. The square knot, one of the simplest patterns, often serves as practice for beginners. Intermediate-level knots like the lotus knot incorporate multiple loops that radiate from a central point, while advanced creations like the ten-section brocade knot challenge even experienced artisans. Master Chen Li, who teaches knotting workshops in Shanghai, emphasizes that “the hands must learn the rhythm before the mind can create beauty. We start students with simple patterns until their fingers develop muscle memory.”

The materials themselves carry significance. Silk, with its luminous quality and strength, remains the preferred medium for ceremonial knots. Contemporary artists sometimes incorporate metallic threads or synthetic fibers for durability in jewelry applications, but traditionalists maintain that natural silk best honors the craft’s heritage. The thickness of the cord also matters—thinner threads allow for more intricate work, while thicker cords create bolder statements.

Symbolism Woven Into Daily Life

Chinese knot art permeated daily existence across social classes. Newborns received protective knots hung above their cradles, while students tied wisdom knots to their book bags before examinations. During the Lunar New Year, households displayed elaborate knot arrangements featuring coins and jade pieces to invite prosperity. Travelers carried simple knot charms for safety on journeys, believing the continuous loops prevented misfortune from entering.

Seasonal celebrations featured specific knot designs. The Dragon Boat Festival saw families creating intricate knot talismans using five-colored threads, while Mid-Autumn Festival decorations incorporated moon-shaped knots. Wedding ceremonies involved the most elaborate knot work, with the bride and groom’s families exchanging gifts wrapped in red silk and tied with double happiness knots that took weeks to create. These wedding knots weren’t merely decorative—they symbolized the inseparable bond between families and the continuous nature of marital commitment.

Businesses integrated knots into their commercial practices. Tea merchants used special packaging knots that identified their product grade, while herbalists employed distinctive knots to seal medicinal packages. Even legal documents sometimes featured sealing knots that served as tamper-evident closures before the widespread use of wax seals. The specific way a knot was tied could indicate everything from the document’s importance to the authority of its sender.

A Craft Nearly Lost and Remarkably Revived

Despite facing near-extinction during China’s Cultural Revolution, Chinese knot art has experienced a remarkable resurgence since the 1990s. The UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage designation in 2008 brought international recognition, spurring government initiatives to preserve the craft. Today, workshops across China teach traditional techniques to new generations, while contemporary artists explore innovative applications that bridge historical tradition with modern sensibilities.

Modern interpretations blend traditional symbolism with contemporary aesthetics. Fashion designers incorporate knot elements into clothing and accessories, while interior designers use large-scale knot installations as statement pieces. Technology has also entered the preservation effort—the World Health Organization has noted the therapeutic benefits of knot-tying for manual dexterity and cognitive function in older adults, leading to its incorporation in some occupational therapy programs.

Artist Liang Jing represents this new generation of knot artisans. Her studio in Beijing creates massive knot installations for corporate lobbies and public spaces while maintaining traditional techniques. “The challenge,” she explains, “is honoring the centuries of meaning while making the art relevant today. When I create a large wall piece for a tech company, I’m using the same knots that once adorned imperial palaces, but the context transforms their message from imperial power to corporate identity and cultural pride.”

Practical Applications and Learning Resources

For those interested in practicing Chinese knot art, beginning requires surprisingly accessible materials. Starter kits containing practice cords, diagrams, and basic tools are available through cultural centers or online retailers. Many communities offer in-person workshops, while video tutorials provide step-by-step guidance for remote learners. The learning curve follows a natural progression from simple to complex, allowing beginners to experience early successes while building toward more ambitious projects.

Beginner projects typically include simple friendship bracelets or decorative tassels using fundamental knots like the overhand knot and cloverleaf pattern. As skills develop, crafters can progress to jewelry-making, home decorations, or garment accents. The Statista research platform reports growing global interest in traditional crafts, with searches for Chinese knot tutorials increasing 40% annually since 2020, indicating a widespread rediscovery of this ancient art form.

Master artisans recommend starting with cotton cords rather than slippery silk, as the texture provides better control for novice hands. Practice sessions of twenty minutes daily yield better results than occasional marathon sessions, as muscle memory develops gradually. Keeping a notebook to record successful techniques and challenges helps track progress. Many practitioners find the repetitive motion meditative, with the focus required creating a natural mindfulness practice that benefits mental well-being alongside technical skill development.

Cultural Significance Beyond Borders

Chinese knot art has transcended its cultural origins to become a global phenomenon. International museums feature knot works in their textile collections, while cultural exchange programs include knot-tying demonstrations. The art form’s mathematical precision has attracted interest from mathematicians and engineers studying its structural properties. The continuous loops without beginning or end resonate across cultures as symbols of interconnectedness, making the art form accessible to international audiences regardless of their familiarity with Chinese culture.

Research published in the Journal of Cultural Heritage documents how knot patterns inform modern design fields, from architecture to product design. The structural integrity of certain knot patterns has inspired engineering solutions in fields ranging from aerospace to medical device development. The aesthetic principles of balance and symmetry found in traditional knots continue to influence contemporary design thinking.

This global appreciation has created new markets for knot artists while ensuring the craft’s continuity. As traditional techniques meet contemporary interpretations, Chinese knot art continues to evolve while maintaining its essential character—transforming simple threads into meaningful connections across time and space. The art form serves as a living bridge between ancient wisdom and modern creativity, demonstrating how traditional practices can find new relevance in a changing world while preserving their cultural soul.

Getting Started: Your First Knots

Beginning your knot-tying journey requires minimal investment but offers rich rewards. Start with a basic kit containing several meters of 2mm cotton cord in various colors, a small foam board, T-pins, and a crochet hook or tweezers for manipulating tight spaces. Choose a well-lit workspace where you can leave your project undisturbed between sessions.

The cloverleaf knot makes an excellent first project. Cut a 40cm cord and anchor the center with a pin. Form three loops clockwise, then weave the working end through each loop in sequence. Tighten gradually, adjusting until symmetrical. This fundamental knot introduces the basic weaving pattern used in more complex designs while producing a satisfying finished product.

As your skills develop, challenge yourself with the Pan Chang knot, known for its endless looping pattern. This intermediate project requires approximately 2 meters of cord and considerable patience. The process involves creating multiple interwoven loops that symbolize eternal love and continuity. Many practitioners find that mastering this knot represents a significant milestone in their technical development.

The Future Woven in Threads

Contemporary knot artists continue pushing boundaries while honoring tradition. Some create architectural-scale installations using reinforced cords, while others incorporate LED lighting or interactive elements. The mathematical principles underlying knot patterns have attracted collaboration with computer scientists developing algorithms for pattern generation. These innovations ensure the art form remains dynamic while preserving its essential character.

Educational programs now introduce knot-tying in schools as both cultural education and development of fine motor skills. The meditative quality of the work provides respite from digital overload, making it particularly valuable in modern life. As one young practitioner noted, “When my hands are busy with knots, my mind finds peace. Each completed knot feels like a small victory in a distracted world.”

The enduring appeal of Chinese knot art lies in its unique combination of aesthetic beauty, cultural depth, and hands-on engagement. From imperial courts to contemporary studios, from functional fastenings to profound symbolism, these intricate loops continue to connect generations. The threads may change—silk giving way to synthetic blends, traditional colors expanding to include modern hues—but the essential language of loops and weaves continues to speak across centuries, carrying forward the wisdom of hands that first learned to make cords dance.

You may also like

The Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartBambooSoundBoost Portable Amplifier

Original price was: $96.00.$66.00Current price is: $66.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartAladdin’s Lamp Heat-Change Purple Clay Tea Pot

Original price was: $108.00.$78.00Current price is: $78.00. Add to cartGuangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cart