In a Beijing museum, a visitor pauses before a Tang dynasty tri-color glazed horse. Its vibrant hues have faded only slightly over thirteen centuries. This is not merely an artifact; it is a conversation in clay, a silent testament to the values, beliefs, and aesthetic sensibilities of a vanished world. Chinese handicrafts, from the humblest bamboo basket to the most intricate cloisonné vase, function as a unique historical lexicon. They record cultural priorities with a fidelity often absent from official chronicles. They are the tangible threads connecting dynastic courts to rural villages, philosophical ideals to everyday life, and ancient techniques to contemporary studios. To understand these objects is to decode a language written in glaze, thread, and wood—a language that speaks of identity, belief, and the human hand’s enduring dialogue with material.

Clay as Chronicle: The Philosophical Journey in Fired Earth

Consider pottery, one of humanity’s most ancient companions. In China, its evolution maps a profound cultural and philosophical journey. Neolithic Yangshao pottery, with its swirling fish and geometric patterns painted in mineral pigments, whispers of animistic beliefs and the rhythms of communal life along the Yellow River. The very act of forming and firing earth into a durable vessel was a foundational technological and symbolic leap, transforming mutable soil into permanent form.

This trajectory leads to the sublime monochromes of Song dynasty celadon—jade-like glazes prized for their restraint, subtlety, and the celebration of natural flaws like “crackle” patterns caused by the kiln’s heat. This dramatic shift from bold, symbolic decoration to an aesthetic of understated elegance mirrors a broader philosophical turn towards Daoist naturalism and Confucian refinement. The form itself became the message, with purity of shape and depth of glaze reflecting an inner moral landscape. Scholar-officials of the Song era saw in these quiet wares a reflection of their own ideals: integrity, humility, and a cultivated appreciation for the inherent beauty of the natural world. The object was no longer just a container but a mirror for the mind.

The narrative in clay expanded with global exchange. A single Ming dynasty blue-and-white porcelain dish tells a story of interconnected worlds. Its coveted cobalt blue pigment, often sourced from Persia, traveled the Silk Road, while its form and decorative motifs—like lotus flowers for purity or mythical *qilin* for good omens—satisfied imperial taste and conveyed specific auspicious meanings. The object becomes a nexus where domestic artistry met foreign influence, frozen in a silica glaze. This tradition of ceramic as cultural carrier continues today. In modern Jingdezhen, the “porcelain capital,” artisans grapple with this legacy. “We are painting with history,” says studio potter Zhang Wei. “When I apply cobalt, I am using the same material that came from the Middle East centuries ago. But today, I might paint a scene of the high-speed rail passing through mountains. The technique is ancient, but the chronicle is ongoing.” This living practice underscores how craft is a dialogue, not a monologue from the past.

The Silk Thread of Social Fabric and Cosmic Order

If clay chronicles broad philosophical shifts, textile arts like embroidery and silk weaving articulate social structures, personal identities, and cosmic beliefs with needlepoint precision. Imperial dragon robes of the Qing dynasty were not simply opulent garments; they were walking diagrams of cosmic order and political hierarchy. Each of the twelve imperial symbols—the sun, moon, constellation, mountains—was meticulously embroidered in a strictly prescribed arrangement, a visual language declaring the emperor’s singular role as cosmic intermediary. The type of dragon, its number of claws (five for the emperor, four or three for nobles), and the accompanying motifs were a rigid code, instantly recognizable to the court. To wear such a robe was to physically embody the state.

Beyond the palace walls, the story becomes more intimate but no less rich. Regional embroidery styles, such as Suzhou’s delicate, pictorial embroidery or Hunan’s bold, colorful Xiang embroidery, served as vibrant markers of local identity. The peonies of Luoyang or the cranes of Sichuan stitched into a woman’s handkerchief or a child’s hat were subtle declarations of home, a portable geography. These were not idle hobbies but essential skills, with patterns and techniques passed matrilineally. The famed ‘Hundred Children’ motif, celebrating fertility and family continuity, was replicated across pillows, scrolls, and robes for centuries, making tangible the central Confucian virtue of familial piety and the desire for a prosperous lineage. Textiles were the canvas on which personal hopes and social values were vividly rendered.

The social function of textiles extended into the very fabric of economic life. Silk production, for centuries a closely guarded state secret, was a major driver of trade and wealth, with the Silk Road acting as a vector for both goods and cultural exchange. According to UNESCO, which has inscribed Chinese sericulture and silk craftsmanship on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, the practice remains “a symbol of cultural identity and continuity,” linking thousands of years of history to present-day communities. The World Health Organization has also noted the psychosocial benefits of such traditional, community-centered crafts, linking them to mental well-being and social cohesion, a value that transcends mere economics.

A Weaver’s Reflection: The Lived Philosophy in Thread

“My grandmother taught me the ‘cloud’ pattern when I was seven,” shares Master Weaver Li Juan, from a village in Zhejiang known for its brocade. “She never spoke of history or culture in abstract terms. She would say, ‘This knot remembers the shape of the mountains behind our old home. This gold thread is for prosperity, but see how it is bound by the blue? That is discipline.’ For her, every inch of fabric was a map of memory and a guide for living. When I work the loom now, I don’t just see threads; I hear her voice explaining the world.” This intimate transmission underscores how craft embodies lived philosophy, passing values through gesture, material, and rhythm, not just precept. The repetitive, meditative act of weaving or embroidering becomes a practice in patience, attention, and connection to one’s heritage, a form of mindfulness long before the term entered modern lexicons.

Beyond Utility: Lacquer, Bamboo, and the Ethos of Making

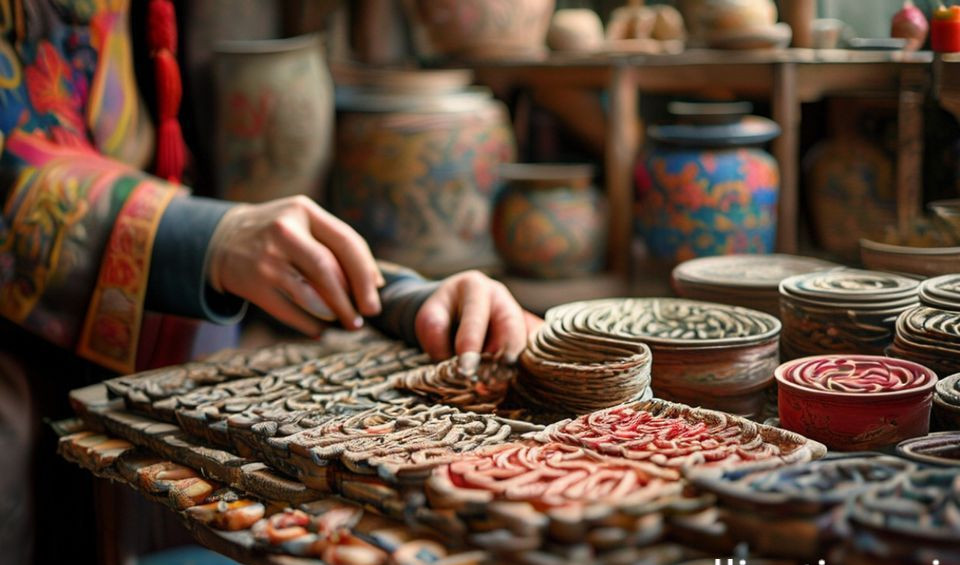

The philosophical depth of Chinese handicrafts extends far beyond pottery and silk into materials that demand a profound partnership between artisan and element. Take lacquerware, a technology perfected over millennia. The process begins with harvesting the sap of the lacquer tree, a substance that is toxic in its raw form and demands respect. A lacquer box from the Warring States period, its hundreds of thin layers built up over months and polished to a deep, resonant glow, speaks of an investment in patience, permanence, and the transformation of a raw material into an object of sublime beauty and durability. Each layer must cure in a humid environment, a slow dance with time that cannot be rushed. The process itself is a lesson in incremental achievement and reverence for material.

Similarly, bamboo weaving embodies the Daoist principle of wu wei—often translated as “effortless action” or “action through non-action.” The artisan must work with the bamboo’s natural strength, flexibility, and grain, not against it. Forcing the material leads to breakage; following its nature leads to resilient, graceful forms. A simple, unadorned Yixing zisha clay teapot, prized by tea connoisseurs, is designed to be seasoned by decades of use, absorbing the aroma of tea to enhance future brews. Its value lies not in ostentatious decoration but in its humble, functional form and its evolving, personal relationship with the user. It is an object that improves with time, embodying a philosophy of cultivation, organic growth, and the beauty of patina.

These crafts resist simple categorization as “art” or “artifact.” They sit at the intersection of utility, beauty, and symbolic meaning. A scholar’s set of carved stone seals was a practical tool for signing documents but also a deeply personal art form expressing literary taste. A paper-cut window decoration for the Lunar New Year served the practical purpose of adorning a home while symbolically warding off evil spirits and inviting luck. Each functional object is imbued with layers of cultural code, making the domestic sphere a site of continuous cultural expression.

The Modern Dialogue: Preservation, Innovation, and Global Resonance

Today, Chinese handicrafts exist in a dynamic tension between preservation and innovation. The challenges are significant: aging master artisans, the pressures of mass production and cheap imitations, and shifting consumer habits that often prioritize convenience over craftsmanship. However, a vibrant, multifaceted revival is underway, driven by cultural policy, renewed market interest from a middle class seeking authentic connection, and a new generation of makers who are both reverent and rebellious.

The Chinese government has implemented systems to identify and support “Intangible Cultural Heritage Inheritors,” providing stipends and platforms for master artisans. This institutional recognition, coupled with a broader policy emphasis on “cultural confidence,” has elevated the status of traditional crafts. Market data reflects this shift; a Statista report on the global luxury market indicates a growing consumer interest in artisanal, story-rich products with provenance, a trend that benefits high-end traditional crafts. This revival, however, is not about mere replication in amber. Contemporary artists and designers are engaging in a creative, sometimes provocative, dialogue with tradition. They might use ancient porcelain techniques to create abstract, modern sculptures that challenge form, employ Suzhou embroidery’s minute stitches to depict photorealistic contemporary urban scenes, or integrate bamboo weaving patterns into sustainable architectural designs. This is not a dilution but an evolution, ensuring the language of craft remains a living, relevant dialect. As designer Lin Ke explains, “My work starts with a question to the past. I ask a Song dynasty ceramic form, ‘How would you live in a Shanghai apartment today?’ The answer comes through the material, but the conversation is new.”

Furthermore, digital platforms and e-commerce have radically democratized access. Platforms like Alibaba’s Taobao or dedicated sites such as “China Craft” feature stores from remote craft villages, allowing a bamboo weaver in Sichuan or a silver jeweler in Yunnan to reach customers in Berlin or New York directly. This fosters economic sustainability for artisans and facilitates a new kind of global cultural exchange, where the story behind the object is as important as the object itself.

Actionable Insights: Engaging with the World of Chinese Handicrafts

For those seeking to understand or incorporate the wisdom of these crafts, moving from passive appreciation to active engagement can be deeply rewarding. The following approaches offer pathways into this rich world.

- Learn to Look Deeply: When viewing a piece, move beyond “it’s beautiful.” Ask: What was its original function? What natural materials were used, and what does that say about its origin? Can you identify a symbolic motif—a bat (fu) for good fortune, a lotus for purity? Resources like the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History or the Victoria and Albert Museum online collections offer superb, searchable catalogs for self-education. Spend time with a single object, imagining the hands that made it.

- Support Ethical Artisanship: If collecting, seek out sellers who provide provenance and work directly with workshops or certified inheritors. Look for pieces that show the slight irregularities of handwork—a barely uneven glaze, a unique wood grain—they tell the true story of human creation. Fair-trade organizations and dedicated online marketplaces for handicrafts are excellent starting points. Remember, purchasing a handcrafted item is a vote for the survival of a skill set.

- Embrace the Philosophy in Daily Life: You don’t need to own a museum piece to practice the principle behind the craft. Use a simple, well-made ceramic bowl for your meals and appreciate its tactile presence and balance. Arrange a single branch in a vase with the mindful asymmetry of a scholar’s garden. The act of mindful selection and engagement with everyday objects is itself a craft, cultivating an appreciation for materiality and intentionality.

- Try a Hands-On Workshop: Many cultural centers, museums, and community studios offer short courses in basics like paper-cutting, knot-tying (Chinese knotting), or calligraphy. The physical struggle to master a simple brushstroke, to feel the resistance of the paper as you cut, or to tie a symmetrical “endless knot” creates a profound, humbling appreciation for the skill embedded in masterworks. It transforms observation into empathy.

The silent conversation held in the glaze of a Tang horse or woven into a brocade continues. Chinese handicrafts are not relics of a static past but a living, adaptive language. They remind us that objects can be vessels for memory, identity, and values, and that the human impulse to shape material with meaning and care is a powerful, enduring form of cultural expression. In holding a well-made object, we momentarily join a conversation across time, touching the patience of the potter, the hope of the embroiderer, and the quiet wisdom of generations who found the universe in a piece of clay or a strand of silk. This dialogue, spanning millennia, invites us not just to look, but to listen, and perhaps, to begin crafting our own small part of the story.

You may also like

Guangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cartBambooSoundBoost Portable Amplifier

Original price was: $96.00.$66.00Current price is: $66.00. Add to cartHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartAncient Craftsmanship & ICH Herbal Beads Bracelet with Yellow Citrine & Silver Filigree Cloud-Patterned Luck-Boosting Beads

Original price was: $128.00.$89.00Current price is: $89.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartThe Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page