In a small Beijing apartment, a grandmother teaches her granddaughter how to secure a precious jade pendant using a traditional double coin knot. This simple moment captures the enduring practicality of Chinese knot art—where beauty and function intertwine as seamlessly as the silk cords themselves. Across China, from rural villages to urban centers, this ancient craft continues to thrive, adapting to modern life while preserving cultural identity.

More Than Ornament: A Legacy of Practicality

While often admired for their decorative appeal, Chinese knots have served practical purposes for over two thousand years. Archaeological evidence shows knotting techniques appearing during the Zhou Dynasty, evolving through successive dynasties into the sophisticated art we recognize today. Fishermen used specific knots to secure nets that could withstand ocean currents, scholars employed them to fasten important scrolls against humidity and wear, and merchants relied on particular patterns to seal documents—each knot type serving as both fastener and authenticator.

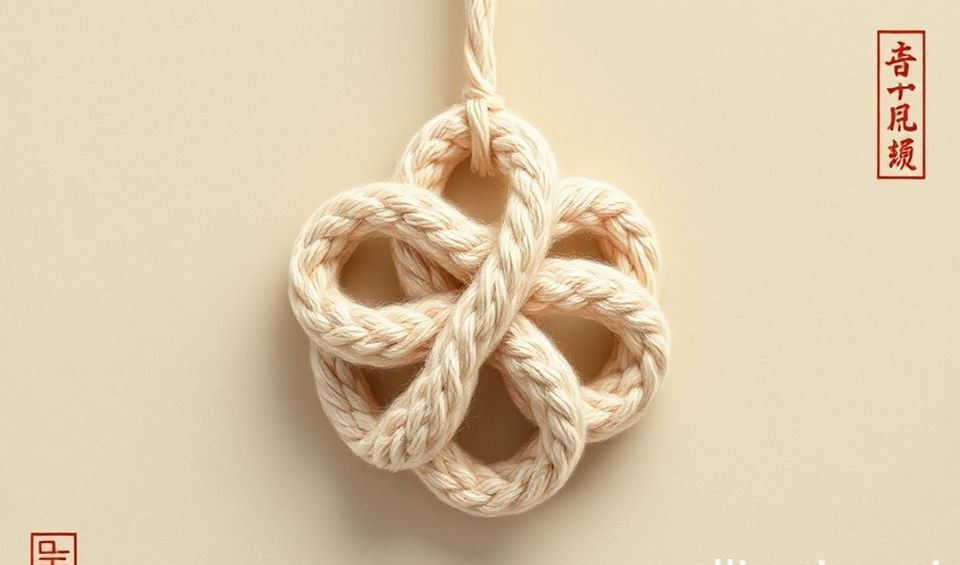

The pan chang knot, with its interlocking structure, proved particularly effective for securing items without slipping—a quality that made it invaluable for everything from tying ceremonial gifts to fastening clothing. This endless knot pattern, sometimes called the “true lover’s knot,” embodies Buddhist concepts of eternity and interconnectedness while providing remarkable physical stability. Modern practitioners continue discovering these functional advantages. A Shanghai-based designer recently noted how the good luck knot provides superior weight distribution when used as a bag handle, while the button knot offers a durable alternative to conventional fasteners. These applications demonstrate how traditional techniques solve contemporary problems.

Li Wei, a third-generation knot artisan from Hangzhou, shares how he adapted traditional methods for modern use: “When a client wanted a secure way to carry their tablet computer, we developed a shoulder strap using multiple pan chang knots. The pattern distributes weight evenly and won’t slip, even when adjusted quickly. The client later told me it had survived three years of daily commuting—that’s the proof of good design.”

Symbolic Language Woven in Silk

Beyond their practical applications, Chinese knots constitute a complex symbolic language where colors, patterns, and materials convey specific meanings. Red cords traditionally signify good fortune and celebration, while gold threads represent wealth and prosperity. The number of loops in a knot carries numerical significance—eight loops for abundance, six for smoothness in life’s journey. This symbolic vocabulary transforms ordinary cord into meaningful communication.

During the Spring Festival, households throughout China display intricate knot arrangements featuring coins, jade pieces, or small bells. These decorations serve dual purposes: bringing auspicious energy while organizing household items. A mother might create a clothes fastener using a double happiness knot for her daughter’s wedding trousseau, embedding blessings for the marriage within a practical item. As noted by UNESCO in their study of intangible cultural heritage, such practices represent “living traditions that communities recognize as part of their cultural heritage,” maintained through continuous reinvention in daily life.

The World Health Organization has documented the therapeutic benefits of such handcrafts, noting in a 2021 report that “repetitive, focused manual activities like knot-tying can reduce stress indicators and improve cognitive function in adults of all ages.” This research validates what practitioners have known for centuries—the meditative rhythm of knot work soothes the mind while engaging the hands.

Learning Through Doing: The Tactile Path to Mastery

The true understanding of Chinese knots comes not from studying diagrams but from handling the cords. Start with basic materials: a meter of rattail cord, scissors, and a flat surface. The cloverleaf knot makes an excellent beginning project—its four loops create a stable base for keychains or curtain ties. Many beginners find that working with their hands creates a meditative state, where muscle memory develops alongside technical understanding.

One craft teacher emphasizes the tactile nature of the learning process. “Students often struggle until they feel the cord’s tension shift,” she observes. “That moment when the knot ‘clicks’ into place—both literally and mentally—is when the art becomes accessible.” This hands-on approach transforms abstract patterns into practical skills. Online tutorials have made the craft more accessible than ever, with platforms hosting thousands of knot-tying demonstrations. However, many practitioners still value in-person instruction for its immediate feedback and cultural context.

Within three practice sessions, most beginners can master two fundamental knots and combine them into simple functional items. The progression from single knots to composite designs mirrors how traditional artisans developed their skills—through repeated application to everyday needs. A university student in Nanjing described her introduction to the craft: “I started with a basic cross knot for my earphones, then progressed to a more complex chrysanthemum knot for a necklace. Each knot taught me something about patience and precision that translated to my studies.”

Contemporary Innovations and Global Reach

Chinese knot art has evolved beyond its traditional boundaries, finding new expressions in fashion, interior design, and even technology. Designers at Shanghai Fashion Week have incorporated elaborate knot work into clothing collections, while architects have used knot principles to create innovative tension-based structures. The mathematical properties of certain knots have attracted interest from engineers studying secure fastening systems.

According to Statista, the global market for artisanal crafts including Chinese knots grew by 14% between 2019 and 2022, reflecting renewed interest in handmade items with cultural significance. International artists have begun incorporating knot elements into their work, creating cross-cultural dialogues. Japanese macramé artists blend Chinese knotting techniques with their own traditions, while European jewelry designers adapt the methods for contemporary accessories.

Chen Yulan, a knot artist based in San Francisco’s Chinatown, has developed a thriving business teaching knot workshops to diverse audiences. “At first, people come for the beauty of the knots,” she explains. “But they stay for the connection—to history, to culture, to their own hands. I’ve had students from Argentina to Norway discover personal meaning in these ancient patterns.” Her experience demonstrates how traditional crafts can build bridges across cultures while maintaining their essential character.

Practical Applications for Modern Life

Integrating Chinese knots into daily life requires minimal materials but offers substantial rewards. Begin with these accessible projects:

- Cable organizers: Use simple overhand knots at intervals along a longer cord to create adjustable ties for electronic cables. The slight friction of the silk prevents slipping without damaging wires.

- Bookmark creation: Weave a flat square knot with colorful cord, adding beads or tassels for weight. These make thoughtful gifts that combine utility with aesthetic appeal.

- Personalized jewelry: Create adjustable bracelets using button knots that slide to fit any wrist. Incorporate birthstone colors or meaningful charms for added significance.

- Home decoration: Craft curtain tiebacks using the cloverleaf knot, which provides secure holding power while adding elegant detail to window treatments.

These projects demonstrate the ongoing relevance of knot art in solving everyday organizational challenges. The materials are inexpensive and portable, making knot-tying an ideal craft for travel or waiting periods. Many practitioners keep a small cord collection in their bags for impromptu creation during spare moments.

Preserving Tradition Through Innovation

As one cultural preservationist remarked during a workshop demonstration: “We’re not just tying pretty shapes. We’re continuing a conversation between hands and materials that began centuries ago. When a teenager uses a butterfly knot to repair a friendship bracelet or an office worker employs a mystic knot to organize cables, they’re participating in that same dialogue—proving that utility needs no translation across generations.”

Museums and cultural centers have recognized the importance of keeping this tradition alive through interactive exhibits. The China National Silk Museum in Hangzhou features a permanent knot-tying station where visitors can create their own simple knots while learning about the history of the craft. Similar programs at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco and the British Museum introduce international audiences to Chinese knot art through hands-on experiences.

Academic institutions have begun documenting the mathematical principles underlying various knots, with researchers from Tsinghua University publishing studies on the structural efficiency of traditional knot patterns. Their work, appearing in journals like Textile Research Journal, demonstrates how ancient solutions continue to inform modern engineering challenges.

The future of Chinese knot art appears secure precisely because it remains adaptable. From grandmothers teaching grandchildren in Beijing apartments to designers in Milan incorporating knot elements into luxury goods, the tradition continues to evolve while maintaining its essential character—proving that some connections only grow stronger with time.

You may also like

Guangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cartBambooSoundBoost Portable Amplifier

Original price was: $96.00.$66.00Current price is: $66.00. Add to cartHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartAncient Craftsmanship & ICH Herbal Beads Bracelet with Yellow Citrine & Silver Filigree Cloud-Patterned Luck-Boosting Beads

Original price was: $128.00.$89.00Current price is: $89.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartThe Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page