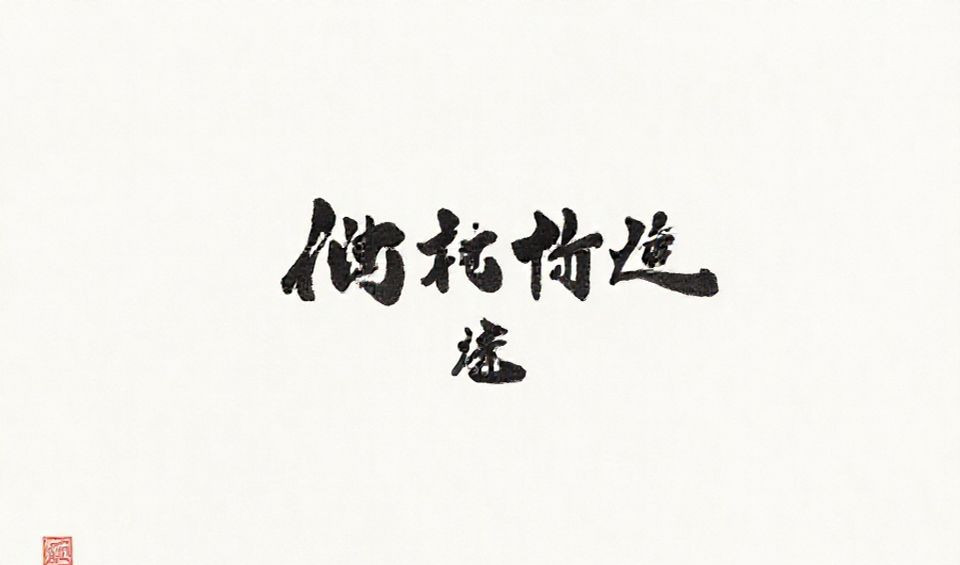

When Wang Xizhi dipped his brush into ink during the Eastern Jin dynasty, he could not have known his characters would survive sixteen centuries. His ‘Orchid Pavilion Preface’ remains the calligrapher’s holy grail—not for its perfect execution alone, but for capturing a moment where art, friendship, and wine flowed together. This is calligraphy’s essence: not merely writing, but time made visible.

The Stroke as Historical Witness

Each major script style emerged from specific historical needs. Seal script’s symmetrical elegance served imperial decrees during the Qin unification. Clerical script’s broader strokes answered the Han dynasty’s bureaucratic demands—easier to write on bamboo slips, faster to read. By the Tang, when Ouyang Xun perfected regular script, standardization had become an imperial project. His ‘Inscription of the Sweet Spring at the Jiucheng Palace’ demonstrates how precision could convey authority without sacrificing beauty.

The evolution of Chinese calligraphy fonts parallels China’s administrative and cultural shifts. During the Song dynasty, the rise of woodblock printing created new demands for legibility and reproducibility, leading to the refinement of standard script. The Ming and Qing periods saw the flourishing of artistic script variations, where personal expression began to outweigh rigid uniformity. These fonts were not static artifacts but living responses to material and social conditions—whether carved on oracle bones, brushed on silk, or printed in books.

Historical records show how calligraphy served as both administrative tool and artistic expression. A Tang dynasty edict requiring standardized script for official examinations created what one scholar called “the first national handwriting standard.” This tension between uniformity and individuality would define calligraphy’s development for centuries, with each dynasty leaving its distinctive mark on the evolution of Chinese characters.

Cultural Values in Ink and Paper

Calligraphy reveals what Chinese culture prized: balance in the composite character ‘yong’ (eternity), which contains all eight basic strokes; spontaneity in Mi Fu’s running script, where ink splatters suggest joyful abandon; restraint in Liu Gongquan’s bony strokes, which contemporaries said ‘showed his upright character.’ The four treasures—brush, ink, paper, and inkstone—were never mere tools. An artisan might spend three years making a single brush, selecting weasel hairs from only the autumn coat when they held ink best.

A modern master, trained in the old manner, observes: ‘My teacher made me copy Yan Zhenqing’s ‘Nephew Memorial’ for two years before allowing me to write my own characters. He said I needed to feel the grief in those thick, anguished strokes—calligraphy is emotion remembered in muscle.’ This continuity, from Tang dynasty mourning to contemporary practice, illustrates how the art sustains cultural memory.

UNESCO’s recognition of Chinese calligraphy as an Intangible Cultural Heritage underscores its role in preserving cultural identity across generations. The practice embodies philosophical principles from Daoism and Confucianism—harmony between empty space and ink, discipline in form, and reverence for tradition. As one practitioner notes, ‘When I write, I am not just making marks. I am conversing with a lineage that stretches back millennia.’

The cultural significance extends beyond the art itself. Calligraphy has historically been one of the four essential arts of the Chinese scholar, alongside painting, music, and board games. Its mastery signaled cultivation and refinement, with emperors and officials alike judged by their handwriting. Even today, beautiful penmanship commands respect in social and professional contexts throughout Chinese-speaking communities.

From Traditional Scripts to Digital Fonts

The transition of Chinese calligraphy into the digital age represents both a challenge and an opportunity. Early computer fonts struggled to capture the fluidity and variation of hand-brushed characters, often resulting in stiff, uniform typefaces. However, advances in font design and vector graphics have enabled the creation of digital fonts that retain the aesthetic qualities of classical scripts while ensuring readability on screens.

Today, designers draw inspiration from historical masterpieces to develop fonts for branding, publications, and user interfaces. For example, the ‘Yan Zhenqing’ font, modeled after the Tang master’s robust regular script, is used in cultural exhibitions and educational materials to evoke authority and tradition. Another font, based on Wang Xizhi’s running script, brings elegance to luxury packaging and invitations.

According to Statista, the global font market is projected to grow significantly, with demand for culturally resonant typefaces rising in parallel. Chinese calligraphy fonts, with their unique balance of artistry and structure, are increasingly sought after for global media and design projects. The challenge lies in preserving the dynamic quality of brushwork while meeting the technical requirements of digital platforms.

Font designer Li Ming describes the process: “When creating a digital calligraphy font, I don’t just scan historical works. I study the pressure variations, the speed of the brush, the way ink spreads on paper. Then I recreate these elements digitally, often spending months on a single character set to capture that essential human touch.”

Practical Applications and Learning Approaches

For those beginning their journey into Chinese calligraphy, start by studying the eight basic strokes of the ‘eternity’ character. Practice these strokes daily to build muscle memory and understand how pressure, speed, and angle affect the line quality. Use a medium-sized brush and practice paper to experiment with different scripts—begin with regular script for its clarity before moving to semi-cursive or cursive styles.

When incorporating calligraphy fonts into digital design, select fonts that match the project’s tone. A corporate report might benefit from a clean, regular script font, while a creative project could use a more expressive running or cursive font. Always test readability at various sizes and ensure proper licensing for commercial use.

Resources like the World Health Organization‘s guidelines on traditional arts for mental well-being highlight calligraphy’s meditative benefits. The deliberate, focused movements can reduce stress and improve concentration, making it a valuable practice beyond its artistic merits. Many practitioners report entering a state of flow during extended practice sessions, where time seems to suspend and mental clarity emerges.

Beginner calligrapher Zhang Wei shares his experience: “I started practicing during a stressful period in my life. The rhythmic motion of the brush, the smell of ink, the focus required—it became my daily meditation. After six months, not only had my handwriting improved, but I felt calmer and more centered in all aspects of my life.”

Preserving Tradition in a Modern World

Despite the digital revolution, the traditional practice of calligraphy remains vibrant. Calligraphy clubs, university courses, and online tutorials ensure that the skills and philosophies behind the art are passed down. Exhibitions of historical works, such as those at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, continue to draw crowds, inspiring new generations of artists and designers.

One calligrapher shares, ‘I practice every morning before work. It grounds me and reminds me of the beauty in discipline. Even when I design digital fonts, I begin with ink and paper—the connection to the hand cannot be replaced.’ This blend of old and new ensures that calligraphy remains a living art, adapting without losing its soul.

Studies published in journals like the Archives of Asian Art document calligraphy’s influence on contemporary visual culture, from advertising to architecture. Its principles of balance, flow, and expression offer timeless lessons for creators in any medium. The resurgence of interest among younger generations, particularly through social media platforms where calligraphy videos attract millions of views, suggests the art form is experiencing a renaissance.

Master calligrapher Chen Xiaodong observes this trend: “I see young people in their twenties coming to my workshops, not because their parents made them, but because they genuinely want to connect with this tradition. They film their practice sessions, share tips online, and create modern interpretations of classical works. This is how traditions stay alive—when each generation makes them their own.”

Global Influence and Cross-Cultural Exchange

Chinese calligraphy fonts have transcended their cultural origins to influence global design trends. International brands incorporate calligraphic elements to convey sophistication and heritage. For instance, luxury fashion houses use script-inspired logos to evoke exclusivity and craftsmanship, while tech companies employ calligraphy principles in interface design to create more organic, human-centered digital experiences.

Educational initiatives, supported by organizations like UNESCO, promote cross-cultural exchanges where calligraphy serves as a bridge between East and West. Workshops and collaborative projects introduce the art’s techniques and philosophies to diverse audiences, fostering mutual appreciation. These exchanges often reveal surprising connections—the gestural abstraction of American abstract expressionism, for example, shares unexpected common ground with cursive script’s emphasis on movement and energy.

As one designer notes, ‘Working with Chinese calligraphy fonts taught me to see space differently. The interplay between character and background is a lesson in composition that applies to any visual medium.’ This global dialogue enriches both traditional practices and modern design, ensuring that the stroke of the brush continues to speak across boundaries and eras.

Graphic designer Maria Rodriguez describes her introduction to calligraphy principles: “I attended a workshop expecting to learn about Asian aesthetics, but what I discovered were universal design principles. The concept of ‘negative space’ in calligraphy revolutionized how I approach layout design. The idea that emptiness could be as meaningful as form changed my entire creative process.”

The Future of Calligraphy Fonts

Looking ahead, Chinese calligraphy fonts face both challenges and opportunities. The development of variable fonts and responsive typography offers new possibilities for dynamic text that changes based on context—imagine digital text that subtly alters its weight and flow based on content emotion or reading speed. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence presents intriguing applications, with systems being trained to generate new calligraphic styles while respecting traditional principles.

However, these technological advances raise important questions about authenticity and preservation. Can algorithms truly capture the spontaneity and emotional depth of human brushwork? Many in the calligraphy community argue that while digital tools offer exciting possibilities, the heart of the art remains in the physical practice—the feel of brush on paper, the smell of ink, the embodied knowledge passed from teacher to student.

Calligraphy educator Dr. Wang Lin takes a balanced view: “We shouldn’t see technology as a threat to tradition. The same concerns emerged when woodblock printing was invented, and again with the typewriter. Each time, calligraphy adapted and found new relevance. The key is maintaining the connection to the fundamental principles—the respect for materials, the understanding of historical context, the cultivation of patience and discipline.”

As we move further into the digital age, the enduring appeal of Chinese calligraphy fonts reminds us of our need for connection—to history, to culture, and to the human hand behind the marks we make. Whether rendered in ink on silk or pixels on screen, these characters carry forward a conversation that began millennia ago, inviting each new generation to pick up the brush and add their voice to the ongoing story.

You may also like

Ancient Craftsmanship & ICH Herbal Beads Bracelet with Yellow Citrine & Silver Filigree Cloud-Patterned Luck-Boosting Beads

Original price was: $128.00.$89.00Current price is: $89.00. Add to cartHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartGuangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cartBambooSoundBoost Portable Amplifier

Original price was: $96.00.$66.00Current price is: $66.00. Add to cartThe Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page