In the quiet corners of traditional kitchens across East Asia, a remarkable transformation occurs—one that connects modern palates to culinary practices dating back over two thousand years. Fermented tofu, known in Chinese as furu or doufuru, represents not merely a foodstuff but a living bridge between generations. This humble ingredient, born from soybeans through careful fermentation, carries within its pungent aroma and complex flavor the accumulated wisdom of countless cooks and artisans.

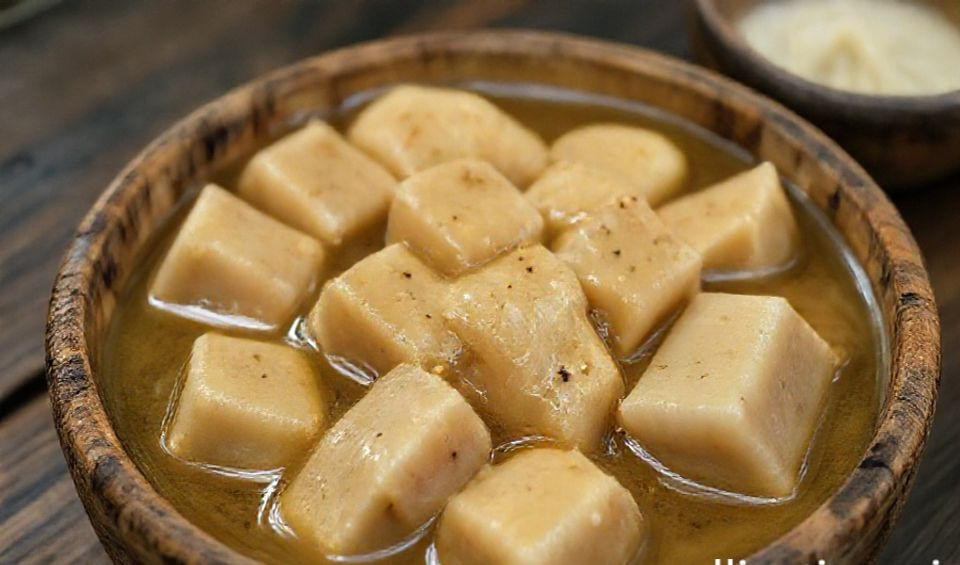

The alchemy begins with fresh tofu pressed to remove excess moisture, creating a dense canvas for microbial artistry. Artisans then inoculate these compacted blocks with beneficial molds like Actinomucor elegans or Mucor species, though traditional producers often rely on wild fermentation from the ambient environment. These microorganisms work their magic over weeks or months in temperature-controlled spaces, breaking down proteins and fats into amino acids and fatty acids that create fermented tofu’s characteristic umami richness. The final product emerges transformed—creamy in texture, intensely savory, and surprisingly versatile in culinary applications from simple condiments to complex sauces that form the backbone of many Asian dishes.

Imperial Beginnings and Monastic Refinement

Historical records from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) contain the earliest references to tofu preservation techniques that would eventually evolve into fermented tofu. During the Wei-Jin period, Buddhist monasteries became crucial centers for developing systematic fermentation methods. Monks, adhering to strict vegetarian principles, perfected ways to enhance tofu’s nutritional profile and flavor through controlled microbial action. Their innovations weren’t merely practical—they reflected a philosophical approach to food that valued transformation and preservation, seeing in the fermentation process a metaphor for spiritual development.

By the Tang Dynasty, fermented tofu had traveled from temple kitchens to imperial banquets, with court documents mentioning specially prepared varieties presented to the emperor. Historical accounts describe elaborate presentations where fermented tofu was served in carved jade containers, its strong aroma contrasting with delicate porcelain. The food historian Dr. Lin Wei notes, “The elevation of fermented tofu from monastic staple to imperial delicacy illustrates how Buddhist culinary practices influenced even the highest levels of society. The Tang court appreciated both its flavor and its symbolic value as a food of spiritual refinement.”

This period saw the development of sophisticated grading systems based on texture, aroma, and appearance. The finest specimens—those with uniform coloration, velvety texture, and balanced saltiness—commanded prices comparable to rare teas. Production methods became more standardized, with detailed records kept of temperature control, brine compositions, and aging durations. These early quality control measures established benchmarks that would influence production for centuries.

Regional Expressions and Cultural Adaptations

As knowledge spread across China’s diverse landscapes, regional variations emerged that reflected local environments and cultural preferences. In Guangxi province, artisans developed a distinctive red variety using rice wine and red yeast, giving the tofu both vibrant color and subtle sweetness. Meanwhile, Sichuan masters incorporated chili and peppercorns, creating a spicy version that mirrored the region’s bold culinary identity. “My great-grandmother stored her fermented tofu in clay pots buried halfway in the earth,” recalls Chen Li, a third-generation producer from Anhui. “She said the soil’s constant temperature gave it a smoother texture than any modern method. We still follow her techniques today, though finding apprentices willing to learn these time-consuming methods becomes harder each year.”

These regional differences weren’t merely matters of taste—they represented intelligent adaptations to specific climates and available resources. Coastal regions often used seawater in their brines, incorporating natural minerals that enhanced the fermentation process. Mountainous areas incorporated local herbs and wild fermentation accelerants like certain tree barks or leaves. In Yunnan province, some producers still use traditional bamboo containers that impart a subtle grassy note to the final product, while Taiwan developed its own unique style using black beans and sesame oil.

The resulting diversity demonstrates how a single technique could blossom into dozens of distinct cultural expressions. From the mild white varieties popular in Jiangsu to the robust, wine-infused types of Zhejiang, each region developed its own signature version. This localization wasn’t accidental—it represented generations of observation and adjustment to local conditions, with knowledge passed down through families and guilds. The variations became so distinct that experienced connoisseurs could often identify a tofu’s region of origin by taste and texture alone.

Nutritional Powerhouse and Health Benefits

Modern nutritional science has begun to validate what traditional practitioners long understood—fermented tofu offers significant health benefits beyond basic nutrition. The fermentation process increases the bioavailability of isoflavones, compounds linked to reduced risk of certain cancers and improved bone health. A World Health Organization report on traditional fermented foods highlights how these processes can enhance nutritional value while preserving food safety through natural antimicrobial compounds produced during fermentation.

The probiotic content of properly fermented tofu supports gut health, contributing to improved digestion and immune function. “I’ve incorporated a small amount of fermented tofu into my daily diet for years,” says nutritionist Maria Chen. “My patients are often surprised when I recommend it, but the combination of high-quality plant protein, probiotics, and isoflavones makes it particularly valuable for those following plant-based diets. The fermentation also creates bioactive peptides that may have additional health benefits we’re just beginning to understand.”

Compared to fresh tofu, fermented versions contain higher levels of certain B vitamins produced by the fermenting microorganisms. The breakdown of proteins during fermentation also makes the amino acids more easily absorbed by the body. However, consumers should be mindful of sodium content, as traditional preparation methods often involve significant salt in the brining process. Some modern producers are addressing this concern by developing lower-sodium versions while maintaining traditional flavors.

The Science Behind the Transformation

The magic of fermented tofu lies in its microbial ecosystem. During the initial fermentation phase, molds like Actinomucor elegans break down the tofu’s structure, creating channels for brine penetration and producing enzymes that transform proteins and fats. This stage typically lasts two to three weeks in controlled environments where temperature and humidity are carefully monitored. The second phase involves aging in brine solutions that may include rice wine, chili, sesame oil, or various spices depending on the regional style.

Scientific analysis reveals that this process generates over fifty distinct flavor compounds, including esters that contribute fruity notes and sulfur compounds that create the characteristic pungency. Research published in the International Journal of Food Microbiology has identified novel peptides formed during fermentation that may have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. The complex microbial ecosystems involved in traditional fermentation are now being mapped using DNA sequencing techniques, revealing surprising diversity in regional variations and helping scientists understand why traditional methods often produce superior results compared to industrial shortcuts.

These scientific insights are helping bridge traditional knowledge with modern food science. Understanding exactly which microorganisms contribute to optimal flavor development allows producers to maintain quality while ensuring safety. They also help explain why certain traditional methods—like aging in specific types of clay pots or using particular brine ingredients—produce consistently better results than modern industrial approaches.

A Living Tradition in Modern Times

Despite industrialization, traditional methods persist in family-run operations that have weathered centuries of social and economic change. At the 150-year-old Wangji Fermented Tofu workshop in Zhejiang, fourth-generation owner Wang Ming still uses wooden molds passed down from his great-grandfather. “We ferment in small batches of no more than fifty jars at a time,” he explains. “The wooden containers breathe differently than plastic or glass, allowing the mycelium to develop more complex flavors over the six-month aging process. Modern factories can produce in days what takes us months, but connoisseurs can taste the difference. Our customers tell us they can detect notes that simply don’t develop in accelerated processes.”

This commitment to traditional craftsmanship ensures that historical knowledge continues to inform contemporary production. Yet these artisans also face significant challenges—rising costs, changing tastes, and the difficulty of attracting new generations to labor-intensive traditions. Some have adapted by developing online sales channels or offering educational workshops that introduce fermented tofu to new audiences. Others have formed cooperatives to share resources and knowledge while maintaining their individual production styles.

The tension between tradition and modernity plays out in interesting ways. While some younger producers are returning to traditional methods after seeing the limitations of industrial approaches, others are finding innovative ways to combine old knowledge with new technology. Temperature-controlled fermentation chambers that mimic traditional cellar conditions, for example, allow for more consistent results while maintaining the essential characteristics of traditionally fermented tofu.

Practical Applications and Culinary Uses

For home cooks interested in exploring fermented tofu, several approaches can make this ingredient more accessible. Start with small quantities from reputable producers—look for products with minimal additives and traditional production methods. The white variety tends to be milder and works well as an introduction, while the red versions offer more complexity for experienced palates. Many Asian markets now carry multiple varieties, and some even offer tasting notes to help customers select the right type for their needs.

In the kitchen, fermented tofu shines as both condiment and ingredient. Mash a cube with sesame oil and scallions for a quick dip for vegetables or a spread for steamed buns. Stir into noodle soups or congee to add depth and umami. For a simple vegetable stir-fry, try replacing salt with mashed fermented tofu—it will add both seasoning and rich flavor. Chef Michael Bao of Brooklyn’s Lotus Garden recommends, “Think of it as Asian blue cheese. It’s strong on its own but melts beautifully into sauces and dressings. I whisk it with rice vinegar and neutral oil for an incredible salad dressing, or mix it with mayonnaise for a unique sandwich spread. The key is starting with small amounts and adjusting to taste.”

Storage is straightforward—keep fermented tofu in its original brine in a sealed container in the refrigerator, where it will keep for months. The brine itself shouldn’t be discarded—it can be used to marinate meats or add flavor to braised dishes. As the tofu ages in your refrigerator, its flavor will continue to develop and intensify, much like a fine cheese. Some enthusiasts maintain that properly stored fermented tofu actually improves with additional aging, developing deeper, more complex flavors over time.

For those feeling adventurous, home fermentation is possible though requires careful attention to hygiene and temperature control. Many traditional producers worry that without proper guidance, home fermenters might create unsafe products. “I understand the interest in DIY fermentation,” says Wang Ming, “but this isn’t sauerkraut. The risks of contamination are higher with tofu fermentation. I recommend people start by appreciating well-made commercial products before attempting their own. If you do try home fermentation, work with someone experienced and pay close attention to cleanliness and temperature control.”

Global Journey and Future Prospects

As global interest in fermented foods and plant-based proteins grows, fermented tofu is finding new audiences beyond its traditional territories. Statista market analysis shows double-digit growth in international sales of Asian fermented foods over the past five years, with particular strength in North American and European markets. Artisanal producers are adapting their marketing to emphasize both the traditional aspects and the modern health benefits, positioning fermented tofu as both a cultural treasure and a functional food.

In Portland, Oregon, a small company called Cultured Joy has begun producing fermented tofu using local organic soybeans and traditional Chinese methods. Founder Jessica Lin says, “Our customers range from Chinese immigrants seeking tastes from home to fermentation enthusiasts who appreciate the complexity. What surprises people is how approachable it becomes when you understand how to use it. We’ve found that once people try it in a well-prepared dish, they become converts. The biggest challenge is overcoming initial hesitation about the aroma.”

Research institutions are also showing renewed interest. The UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list now includes several food fermentation traditions, raising awareness of their cultural significance. Scientists are studying how these traditional methods might inform modern food production, particularly in developing sustainable protein sources. The microbial communities involved in tofu fermentation represent a valuable genetic resource that could contribute to developing new fermentation technologies for plant-based foods.

The future of fermented tofu likely lies in balancing tradition with innovation. While industrial production will continue to dominate the mass market, artisanal producers are finding niches among consumers who value craftsmanship and authenticity. The same microbial processes that preserved tofu for ancient monks may yet contribute to solving modern nutritional challenges—a testament to the enduring wisdom contained in this humble food. As climate concerns drive interest in sustainable protein sources, fermented tofu’s low environmental impact and high nutritional value position it well for continued global expansion.

From imperial courts to monastery kitchens, from rural farmsteads to urban condiment shelves, fermented tofu has maintained its essential character while adapting to countless contexts. Its continued evolution reflects both respect for tradition and openness to innovation—qualities as valuable in our approach to food as they are in life itself. The story of fermented tofu continues to be written in kitchens around the world, one carefully tended clay pot at a time, as new generations discover the depth and complexity contained within these simple soybean cubes.

You may also like

The Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartBambooSoundBoost Portable Amplifier

Original price was: $96.00.$66.00Current price is: $66.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartAladdin’s Lamp Heat-Change Purple Clay Tea Pot

Original price was: $108.00.$78.00Current price is: $78.00. Add to cartGuangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cart