In the still halls of museums, amid flawless monochromes and intricate blue-and-whites, a different kind of beauty whispers. It lives in the delicate web of fractures veiling Song dynasty Guan ware—a surface not of smooth perfection, but of intentional, celebrated flaw. This is Chinese crackle glaze, where porcelain breathes through a thousand hairline fissures, each one a testament to a philosophical embrace of nature’s impermanent hand. More than a decorative technique, it is a physical manifestation of a worldview, a dialogue between human intention and the uncontrollable forces of the kiln. From its origins in imperial China to its profound influence on global aesthetics, the story of crackle glaze is a journey into the heart of finding profound beauty in controlled accident.

The Aesthetics of Wabi-Sabi, Centuries Before the Term

Long before Japanese tea masters codified wabi-sabi—the appreciation of transience and imperfection—Chinese potters of the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD) were mastering its principles in clay and fire. Their pursuit wasn’t accident, but alchemy. The process hinges on a deliberate mismatch. The potter selects a clay body and formulates a glaze with a different coefficient of thermal expansion. As the fired piece cools in the kiln, the glaze contracts more than the clay body beneath it. This creates immense tensile stress, which is relieved by the formation of a network of tiny cracks. The potter’s genius lay in controlling this inevitable failure, guiding it from a flaw into a feature.

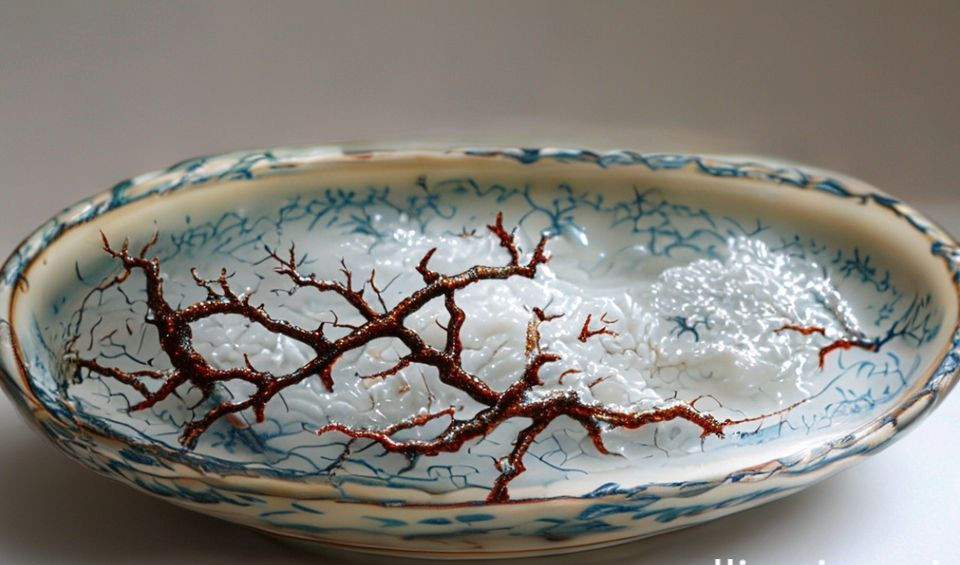

The result was not failure, but a captured moment of tension, a permanent record of thermal conversation. A single Guan vase might display two distinct crackle patterns: the larger, darker ‘ice crack’ (binglie) and a finer, golden ‘crab’s claw’ (xiezhao) network. To accentuate this delicate web, potters would often stain the cracks. They might rub ink, ochre, or other pigments into the fissures after firing, allowing the color to seep deep into the glaze’s capillaries, making the pattern pop against the base color. This practice highlighted the crackle not as something to conceal, but as the very focus of the object’s beauty. It was an aesthetic found not in defiance of material nature, but in profound collaboration with it, a concept deeply rooted in Daoist philosophy.

Imperial Patronage and the Language of Lines

The crackle’s journey from kiln curiosity to cultural icon was cemented by the most discerning of tastes: that of the imperial court. Emperor Huizong (1082–1135), the aesthete-ruler whose reign ended in catastrophe, was a pivotal figure. A renowned painter, calligrapher, and patron of the arts, Huizong’s love for the subtle, the refined, and the naturally resonant elevated crackle ware to the highest echelon. Under his patronage, the crackle became more than texture; it became a language. The imperial workshops, like the famed Guan (official) kilns, pursued a level of subtlety and control that defined the Song aesthetic ideal.

The patterns were read as microcosmic landscapes—evoking frozen rivers, cracked winter ice, or the fissures in ancient stone. They referenced the Daoist concept of ziran (spontaneous naturalness), where human artifice merely sets the stage for nature’s final, unpredictable act. The potter provided the conditions, but the kiln and the materials determined the final pattern. This acceptance of chance within a controlled framework was a powerful metaphor for navigating life itself. By the subsequent Ming dynasty, the technique was further systematized. Crackle size and color became codes denoting different ware grades and styles. The famed ‘Ge’ ware, its crackle often stained a deep, dramatic black, was described as possessing the ‘gold thread and iron wire’ pattern, a poetic metaphor for resilient strength contained within apparent fragility.

A Glimpse Through the Glaze: The Frick’s Celestial Vase

To understand this philosophy made tangible, consider a single 12th-century bottle vase, now residing in New York’s Frick Collection. Its shape is simple, elegantly swelling from a narrow base. Its celadon glaze is the soft, gray-green color of quiet sky after rain. But its surface is alive—a dense, fine mesh of cracks, like the first skin of ice on a pond or the intricate veining on a leaf. Conservators note how later hands gently rubbed pigment into these fissures, not to repair, but to honor and enhance the pattern laid down by the kiln centuries before.

This object isn’t merely a container; it is a landscape painting in three dimensions, its craquelure mapping the invisible forces of contraction and release that played upon it in the fire. It embodies the complete Song dynasty worldview where artistic perfection was found in a respectful dialogue with process and material, not in its denial. As the scholar-collector R. L. Hobson once observed, “The Chinese potter did not seek to hide the crackle; he learned to predict it, to guide it, and finally to demand it as the essential soul of the glaze.” This demand transformed a technical challenge into one of China’s most enduring aesthetic exports.

The Science Behind the Poetry

While deeply philosophical, the creation of crackle glaze is also a precise science of materials engineering. The key variable is the difference in thermal expansion between the ceramic body and the glaze. Potters historically manipulated this through recipe. Using a clay high in silica and low in alumina for the body, paired with a glaze high in alkali and low in silica, reliably produced the desired stress. The cooling rate was another critical lever. Rapid cooling increased stress, often leading to a finer, more numerous crackle, while slower cooling could produce larger, more dramatic fissures.

Modern analysis, using tools like scanning electron microscopy, allows us to see this interplay in stunning detail. Researchers can examine the depth and path of the cracks, understanding how they propagate through the glaze layer. This scientific perspective doesn’t diminish the art but enriches it, revealing the incredible empirical knowledge Song potters developed through centuries of experimentation. A study published in the Journal of the American Ceramic Society on the microstructure of classic crackle glazes underscores how these ancient artisans achieved consistent, beautiful results through a sophisticated, if unwritten, understanding of material science. Their mastery lay in manipulating chemistry and physics to reliably produce what appeared to be a beautiful accident.

Contemporary potters continue to explore this science. Many share glaze recipes and firing schedules online, democratizing knowledge that was once a closely guarded secret of imperial kilns. The variables are endless: the specific minerals in the clay, the purity of the glaze components, the thickness of the glaze application, the peak temperature of the kiln, and the precise curve of the cooling cycle. Each adjustment writes a new sentence in the visual language of cracks.

A Global Dialogue: From Jingdezhen to the World

The influence of Chinese crackle glaze radiated far beyond its borders along the Silk Road and maritime trade routes. It became a highly sought-after export, inspiring potters across Asia. In Korea, it influenced the subdued aesthetics of Goryeo dynasty celadons, which often featured subtle, elegant crackling as a mark of refined taste. In Japan, the philosophy and look of Song crackle ware resonated deeply with the emerging wabi-sabi sensibility of the Muromachi period tea ceremony. Tea masters prized Chinese cracked celadon and temmoku ware, seeing in their imperfections a profound beauty and humility perfectly suited to the contemplative space of the tea room. The Japanese term for this crackle pattern, kan-nyū, directly references its Chinese origin.

This global fascination never truly faded. In the 18th century, European porcelain manufactories, from Meissen to Sèvres, went to great lengths to imitate the “crackled” look, seeing it as the epitome of exotic Eastern refinement. They developed their own techniques, sometimes even painting crackle patterns onto the glaze—a literal imitation that missed the philosophical point but testified to the style’s powerful allure. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London holds several such European attempts, which speak to a centuries-long cross-cultural conversation about beauty.

Today, the legacy continues vibrantly in the studios of contemporary ceramic artists worldwide. They may not be seeking to replicate Guan ware exactly, but they harness the same principle—embracing the unpredictable beauty of the kiln. Artists like Edmund de Waal use crackle glazes to create minimalist vessels that speak of history and memory. Others use dramatic, large-scale crackle on sculptural forms, pushing the technique into new expressive territories. As modern ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu stated, “In the kiln, you are not the boss. The fire is the boss.” This sentiment would have been intimately familiar to a Song dynasty potter tending the dragon kilns of Longquan.

Preservation and the Marks of Time

The very nature of crackle glaze—a network of physical fissures—makes it susceptible to the passage of time in a way a flawless glaze is not. Dirt, oils, and pigments can accumulate in the cracks, altering the piece’s appearance. For museum conservators, this presents a unique challenge. Is the staining part of the object’s history to be preserved, or a later accretion to be cleaned? The decision is never straightforward and is deeply informed by the object’s journey.

This interaction with time is, ironically, part of its intended beauty. Many collectors appreciate how a crackle glaze teacup develops a richer personality with use, as tea slowly darkens its fine lines, creating a personal map of every brew. This echoes the original practice of staining cracks with ink. It represents a continuation of the dialogue between the object and the world, a concept celebrated in Japanese aesthetics as sabi, the beauty of aged patina. Organizations like UNESCO, which works to safeguard intangible cultural heritage, recognize that the value of such crafts lies not just in the object, but in the continuum of knowledge, use, and meaning that surrounds it.

Bringing the Philosophy Home: Practical Appreciation and Application

You don’t need to be an emperor or a master potter to engage with the beauty of crackle glaze. Its philosophy offers practical insights for appreciation, collection, and even for daily life.

Developing a Discerning Eye

When you encounter crackle glaze in a museum or a shop, don’t just glance. Get close. Observe how the light catches the fine lines. See if you can detect staining in the cracks—is it an even, deliberate application or an uneven accumulation from age? Try to follow the path of a single fissure as it branches and travels across the surface. Is it a chaotic spiderweb or an orderly grid? Each pattern is unique. Look for the relationship between the form of the vessel and the pattern of the crackle. On a rounded belly, the cracks often form a spiderweb radiating from a central point; on a straight neck, they may run vertically like rain.

Seeking Out Modern Interpretations

Visit galleries, craft fairs, or online marketplaces featuring contemporary ceramics. You’ll find artists using crackle glazes in bold, new ways—on sculptural forms, with vibrant colors like cobalt blue or rust red, or combined with other textures like matte glazes or raw clay. Purchasing a piece from a working potter connects you directly to this thousand-year-old lineage and supports its living evolution. It makes the tradition tangible in a modern context.

Embracing the “Flaw” in Creative Practice

The crackle glaze philosophy is a powerful metaphor for any creative or life endeavor. It invites you to leave room for the happy accident. Control the process—prepare your canvas, practice your scales, plan your garden—but don’t fear the moment where the material, the instrument, or the situation introduces its own variable. A warp in the wood, a unexpected chord progression, a seedling that volunteers in a new spot—these are the “crackles” that give a creation its distinctive character and soul. As a potter might say, you learn to set the conditions for beauty, but you must surrender to the final act.

Care and Connection

If you own a piece with crackle glaze, understand that its porous, cracked surface can trap oils and dirt. Care for it gently. Hand-wash with a soft cloth and mild detergent, avoiding abrasive scrubbers or dishwashers with harsh detergents. Some enjoy the way tea or use can gently stain the cracks over time, adding a personal patina, much like the ink rubbed into ancient pieces. This is a choice about whether you see the object as a static display piece or a living participant in your daily rituals. If you prefer to keep the original appearance, simply dry it thoroughly after washing.

The enduring whisper of crackle glaze across centuries is a testament to a timeless idea. In a world often obsessed with sterile perfection and flawless finishes, it offers a powerful counter-narrative. It reminds us that beauty is not static but dynamic, born from the interaction of control and chance, intention and accident. It finds elegance in evidence of process, history written in lines of tension. From the imperial courts of the Song to a humble, well-used cup on a modern table, it continues to speak of a beauty that is deeper, wiser, and more resonant because it acknowledges—and celebrates—the fundamental, graceful impermanence of all things.

You may also like

Ancient Craftsmanship & ICH Herbal Beads Bracelet with Yellow Citrine & Silver Filigree Cloud-Patterned Luck-Boosting Beads

Original price was: $128.00.$89.00Current price is: $89.00. Add to cartHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cartGuangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cartAladdin’s Lamp Heat-Change Purple Clay Tea Pot

Original price was: $108.00.$78.00Current price is: $78.00. Add to cartThe Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page