In the vast narrative of Chinese history, emperors and philosophers often claim the spotlight. Yet beneath their towering legacies lies another story—one written in silk thread, bronze patina, and fired clay. It is the story of techniques perfected not in courts, but in workshops; of knowledge passed not through edicts, but from master to apprentice. This perspective shifts the focus from abstract principles to the concrete lives and decisions of individuals whose skilled hands built civilizations. Their innovations, born from necessity and refined by generations, created objects of both sublime beauty and astonishing durability. These ancient Chinese techniques were not static recipes but living traditions, adaptive bodies of knowledge that responded to material constraints, environmental conditions, and a deep philosophical understanding of the natural world as an interconnected system.

The Magistrate’s Manuscript and the Paper That Held It

In a quiet county archive in Zhejiang, a water-stained ledger from the Ming dynasty tells two stories. The first is administrative: records of grain taxes from 1583. The second is technological, embedded in the very fiber of the pages. The paper, made from mulberry bark and bamboo, shows no significant brittleness after four centuries. Its survival is not accidental. It points directly to a papermaker named Li Wen, whose family workshop supplied the local magistrate’s office for three generations. A single note in a later margin mentions him by name, praising the ‘durability of Li’s sheets’ during a particularly damp season.

Li Wen’s technique, a guarded secret, involved a profound understanding of organic chemistry long before the discipline had a name. The prolonged fermentation of the mulberry and bamboo pulp broke down rigid plant fibers, making them pliable and interlocking. The careful treatment with alkaline lye, derived from plant ashes, neutralized natural acids that would otherwise cause the paper to yellow and crumble over decades. This process, demanding patience and precise observation, transformed perishable plant matter into a matrix capable of outlasting dynasties. This ledger, a mundane bureaucratic tool, became the unintended testament to a craft that allowed history to physically endure. Papermaking, one of China’s Four Great Inventions, was more than a medium for writing; it was a victory over time itself, a democratization of record-keeping that shifted history from monumental stone to portable, reproducible sheets.

The implications were global. As papermaking knowledge traveled, it revolutionized communication, administration, and art across Eurasia. Yet the foundational principle remained: a deep, almost intimate collaboration with organic materials. Modern paper conservation still grapples with the acidic wood-pulp paper of the 19th and 20th centuries, which deteriorates far faster than Li Wen’s alkaline sheets. His work offers a clear lesson in sustainable design—by understanding and working with a material’s innate properties, we can create objects built for permanence, not planned obsolescence.

Casting Faith: The Bell of Eternal Harmony

The great bronze bell hanging in the remote Cloud-Dwelling Monastery weighs over eight hundred kilograms. Its clear, deep tone has called monks to prayer since 1420. The story of its creation survives in the monastery’s own chronicles, which detail the arrival of master founder Zhang Guo. He lived in a temporary furnace shed for seventy-nine days. The chronicle describes his precise ritual: how he layered the clay mold with horse hair and fine ash to allow gases to escape, how he calculated the alloy of copper, tin, and lead not by written formula, but by the color of the molten metal in the fire—a deep, shimmering orange-red indicating the perfect temperature.

The most telling detail concerns a flaw. After the first casting failed, leaving a fissure, Zhang insisted on breaking the mold entirely and starting anew. The abbot, anxious about cost and time, pressured him to simply recast the missing section. Zhang refused. ‘The sound will have a sickness,’ he is recorded as saying. His insistence on a single, perfect pour was not just technical dogma; it was an ethical stance on integrity, where the quality of the bell reflected the purity of the faith it served. This holistic view, where metallurgy, acoustics, and spirituality were inseparable, is central to understanding ancient Chinese techniques. The bell was not merely an object but a resonant body, its tone intended to harmonize with the cosmos.

Zhang Guo’s process—from the lost-wax casting method to his intuitive alloying—exemplifies a knowledge system where empirical skill and philosophical principle were fused. This approach to metallurgy produced not only ritual objects but also advanced agricultural tools, weaponry, and coinage that stabilized economies. The technique required systemic thinking: sourcing ores, managing massive labor and fuel resources for furnaces, and understanding the physics of sound and vibration. It was an enterprise that connected mining, chemistry, logistics, and art. Zhang’s story underscores a timeless principle: the integrity of the process is non-negotiable, for it is indelibly written into the final product, whether as a flaw or a perfect, enduring tone.

The Weaver’s Code: Silent Language in Silk and Stitch

While bronze and paper offer grand narratives, the story of silk reveals a technique of breathtaking miniaturization and global consequence. The cultivation of silkworms (*Bombyx mori*) and the unreeling of their continuous filament, a kilometer long from a single cocoon, was a Chinese monopoly for millennia. The technique demanded an almost sacred routine, as the silkworms’ health was exquisitely sensitive to temperature, noise, and even strong odors. But the true genius unfolded on the loom. Complex patterns—like the iconic *kesi* or cut silk tapestry weave—were not printed or embroidered but woven directly into the fabric. Each color change required an individual bobbin, making the process agonizingly slow. A single robe could take years to complete.

This technical marvel was also a language. Patterns were not arbitrary. Dragons symbolized imperial authority, clouds represented good fortune, and specific geometric motifs denoted rank and office. The technique itself enforced this language; the density of the weave, the tightness of the twist in the thread, and the complexity of the pattern were direct indicators of status and wealth. As the UNESCO Silk Roads Programme documents, this technology did not just create luxury goods; it forged the first transcontinental trade network, carrying not just bolts of cloth but also ideas, religions, and artistic motifs from Xi’an to Rome. The weaver at her loom was an unwitting geopolitical actor, her skill fueling an engine of cultural and economic exchange that shaped the ancient world.

The logistical scale was immense. Imperial workshops employed thousands. The technology’s secrecy was a state matter, with harsh penalties for smuggling silkworms or eggs beyond China’s borders. When the knowledge finally diffused, it adapted to local contexts, but the original Chinese techniques set the global standard for quality. Silk production exemplifies a closed-loop, biological technology: mulberry trees fed silkworms, whose waste fertilized the trees, and the final product was both priceless and biodegradable. It stands as an early model of a value chain that integrated agriculture, animal husbandry, and high art into a sustainable, though highly secretive, industry.

A Restorer’s Insight: “When I work on a Tang dynasty silk painting,” says modern conservator Dr. An Xia, “I’m not just seeing colors and forms. My fingers feel the decisions of the weaver—the tension of the warp, the choice to use a twill weave for strength in a section of heavy pigment. One fragment I treated had a nearly invisible repair made with a hair-fine thread, a stitch taken perhaps a thousand years ago by another pair of hands trying to preserve it. That moment of repair is as much a part of the technique as the original creation. It’s a conversation across time, between craftspeople.”

The Alchemy of Clay: From Terracotta Warriors to Celestial Bowls

The silent Terracotta Army of Xi’an, with its thousands of unique, life-sized figures, is a testament to logistical and technical prowess on an industrial scale. Yet the quieter, more pervasive triumph of Chinese ceramic technique lies in the humble yet revolutionary development of high-fired stoneware and porcelain. The quest for the perfect, resonant, white ceramic—later dubbed “white gold” in Europe—drove centuries of innovation. It was a pursuit that blended geology, thermodynamics, and artistry.

The key was Kaolin, a pure white clay, fired in kilns reaching temperatures over 1,300°C. But temperature alone was not enough. Potters in centers like Jingdezhen mastered the control of atmosphere within the kiln. A reduction atmosphere, starving the fire of oxygen, could transform iron impurities in the clay from rusty red to celestial blue or jade green, creating the iconic hues of Longquan celadon. The technique of underglaze painting, where cobalt-blue designs were painted on the unfired body and then sealed under a clear glaze, demanded perfect timing. The pigment could blur or run if the glaze formulation or firing cycle was even slightly off.

These were not accidents of the kiln but calculated results, achieved through meticulous record-keeping and the transmission of hard-won knowledge. According to analyses of trade goods, porcelain became China’s premier export for centuries, its technical specifications—non-porous, hygienic, and beautiful—setting a global standard that still influences ceramic production today. The World Health Organization emphasizes the importance of non-porous surfaces for hygiene, a quality porcelain inherently provided. The development of porcelain represents a pinnacle of material science, where artisans, through relentless experimentation, transformed earth into a substance that defined luxury, utility, and cross-cultural desire for half a millennium.

Enduring Wisdom: Principles for a Modern World

The legacy of these techniques is more than museum pieces; it offers a mindset applicable to modern challenges in sustainability, craftsmanship, and innovation. The core principles observed—deep material intimacy, systemic thinking, and an ethic of long-term integrity—provide a stark contrast to today’s disposable culture and offer actionable insights.

1. Observe and Adapt to Material Nature

Zhang Guo read the fire’s color. Li Wen understood the chemistry of plant fibers. They worked *with* their materials, not against them. This principle of deep observation is the bedrock of biomimicry and the circular economy. Modern designers can apply this by conducting thorough life-cycle analyses of materials, choosing those that are abundant and recyclable, and designing products for easy disassembly. Just as the papermaker selected mulberry for its long, strong fibers, modern creators can select materials based on their inherent strengths and afterlife, moving beyond brute-force engineering to elegant, symbiotic design.

2. Integrity of Process Defines the Outcome

Zhang Guo’s refusal to patch the bell is a parable for quality that resonates in every field. Shortcuts in process—whether in software code, construction, or food production—inevitably manifest as flaws, security vulnerabilities, or structural weaknesses. In an age of rapid iteration, this ancient principle advocates for a stage of deliberate, thoughtful prototyping and testing. It champions the idea that a well-defined, respected process is the most reliable path to excellence. This might mean protecting creative or development timelines from arbitrary compression, or valuing the skilled labor that ensures quality at each step.

3. Knowledge is Embedded and Experiential

These techniques were rarely fully codified in texts. They lived in the hands, eyes, and instincts of the artisan, passed through apprenticeship. This tacit knowledge—the “feel” for a material or process—is invaluable yet vulnerable in a digital age. It underscores the enduring importance of mentorship, hands-on learning, and the preservation of craft lineages. In fields from surgery to advanced manufacturing, pairing theoretical knowledge with supervised, practical experience remains irreplaceable. Organizations can foster this by creating formal mentorship programs and valuing the knowledge of experienced practitioners, ensuring that critical intuitive skills are not lost.

4. Seek Harmony Between Function and Meaning

A bell was for calling to prayer, but its sound aimed for cosmic harmony. Ceramics were for eating, but they embodied aesthetic and philosophical ideals. This fusion of utility and deeper significance can elevate modern product design beyond mere functionality. It asks: does this object merely perform a task, or does it also enrich daily life, foster connection, or reflect sustainable values? A well-designed tool feels good in the hand; a thoughtfully crafted space affects mood and interaction. This principle encourages creators to imbue their work with layers of value—emotional, aesthetic, ethical—making objects not just used, but cherished and maintained across time.

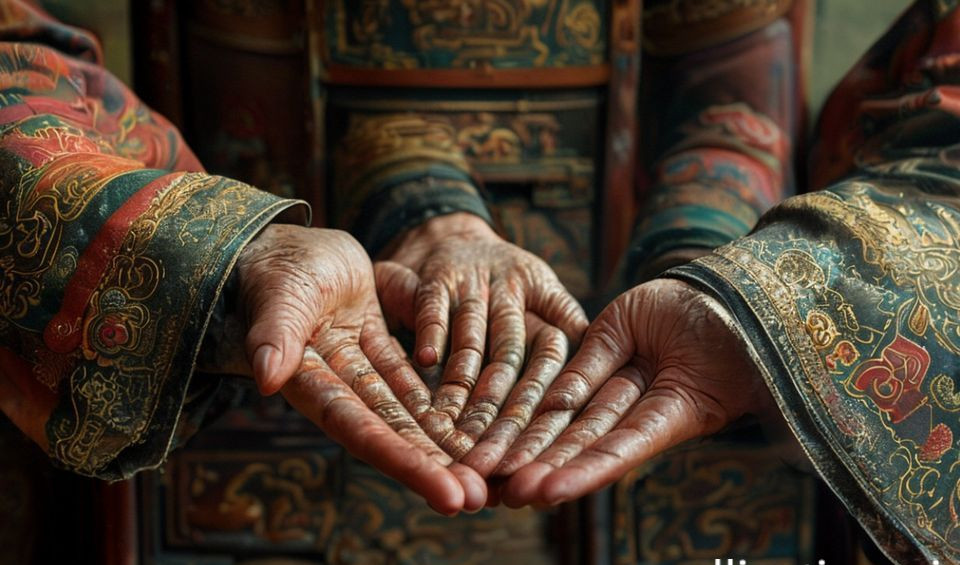

The Human Hands That Shape Eternity

The story of ancient Chinese techniques is ultimately a human story. It is about Li Wen’s pride in paper that could withstand the damp, Zhang Guo’s stubborn pursuit of acoustic purity, and the unnamed weaver whose repair stitch joined a millennium-long conversation. Their work, grounded in patient observation and relentless refinement, created legacies that have endured not in spite of time, but because they were engineered in a dialogue with it.

These objects whisper that the most profound technologies are those that bind utility to beauty, process to principle, and the human hand to the materials of the earth. They demonstrate that innovation is not merely about disruption, but often about deep, cumulative understanding. In an era facing crises of sustainability and purpose, this ancient, embodied wisdom—where every action carries the weight of consequence and the hope for permanence—offers a guiding philosophy. It reminds us that true mastery lies not in dominating nature, but in learning its language, and that the most enduring creations arise from a harmony of skill, integrity, and respect for the material world.

You may also like

Guangxi Zhuang Brocade Handmade Tote – Ethnic Boho Large-Capacity Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $172.00.$150.00Current price is: $150.00. Add to cartHandwoven Zhuang Brocade Tote Bag – Large-Capacity Boho Shoulder Bag

Original price was: $178.00.$154.00Current price is: $154.00. Add to cartBambooSoundBoost Portable Amplifier

Original price was: $96.00.$66.00Current price is: $66.00. Add to cartThe Palace Museum Paper-Cut Light Art Fridge Magnets: Chinese Cultural Style Creative Gift Series

Price range: $27.00 through $36.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageAncient Craftsmanship & ICH Herbal Beads Bracelet with Yellow Citrine & Silver Filigree Cloud-Patterned Luck-Boosting Beads

Original price was: $128.00.$89.00Current price is: $89.00. Add to cartAncient Craft Herbal Scented Bead Bracelet with Gold Rutile Quartz, Paired with Sterling Silver (925) Hook Earrings

Original price was: $322.00.$198.00Current price is: $198.00. Add to cart